Beware: New Danger to Medicare System

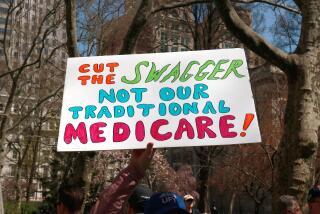

The Medicare system of health benefits for the aged is one of the areas that will merit close scrutiny when the Administration presents its budget for fiscal 1988. Well-placed leaks that are currently appearing in the press are clear indications of an important disagreement within the Administration.

One irresponsible plan being proposed by the Office of Management and Budget would start a dangerous move away from the present system of paying physicians on the basis of the services that they provide. Under the present system, doctors who treat hospitalized Medicare patients bill those patients for the services that they provide, and Medicare pays 80% of the total charge. For low-income patients the rest is paid by Medicaid (Medi-Cal in California); many middle-income patients rely on private insurance to fill in most of the remaining charges.

Under the OMB’s most general proposal, Medicare would pay the hospital a fixed amount per patient for physicians’ services for each type of patient care, and would leave it to the hospital to divide that fixed amount among the different doctors who care for the patient. The amount for each patient would depend on the diagnosis, not on the amount of care received.

After press reports of this proposal and of the objections raised by Health and Human Services Secretary Otis R. Bowen, the OMB plan has been scaled back so that the fixed fee would apply only to the services of radiologists, anesthesiologists and pathologists. Although the cost savings under the revised plan have shrunk to only $500,000 over five years, OMB staff members support it as a first step toward their more general fixed-payment system.

The new proposal is a step that could lead only to patient neglect. Such a shift toward fixed physician payment per hospital admission would distort the pattern of hospital care, denying some patients the services that they should have while inducing physicians to seek unnecessary hospital admissions for others.

If physicians do not receive any extra compensation for giving these Medicare patients additional services, they will be tempted to cut back on their care and to treat additional patients as a way of making up the income that the government has taken away. This proposal would increase pressure to discharge each patient more quickly so that new patients could be admitted and additional fees earned.

If this occurs, the bureaucrats may press for a British-style capitation system in which the doctors are either salaried employees of the hospitals or are paid a fixed fee per person over age 65 regardless of how much care they receive. We risk trading our current high-quality pluralistic system of medical care for a government system in which neither patients nor physicians will be able to choose the amount of care to be provided.

The other part of the Medicare dispute concerns the concept of insuring for catastrophic illness. There is now a limit on the total amount that Medicare will pay for an individual patient. For costs exceeding that amount, patients must pay the bills themselves or through private insurance. Only after individual resources are exhausted can a patient turn to Medicaid.

Secretary Bowen has proposed expanding Medicare to cover all expenses in excess of $2,000 a year in return for an increased monthly Medicare premium. The insurance premium would in principle be set to cover the costs of the program. Under the Bowen plan, no one would risk the catastrophe of losing all of his or her resources for retirement because of a single illness.

An important argument against this proposal is that patients will demand too much care if they are no longer responsible for payments. It is certainly true that when care is free there is continuing pressure for increased spending. But there is a way to control demand while implementing this very good concept.

The way to reduce the excessive use of medical services by Medicare patients is to maintain compulsory cost-sharing for those who can afford it. The upper limit for such cost-sharing should vary with the income of the patient. Because each patient would pay part of every medical dollar up to a certain amount that would depend on his income, there would be an effective incentive to avoid unnecessary medical services.

A further change in the current system would strengthen this cost-consciousness. Although Medicare now pays only 80% of doctors’ bills as a way of limiting unnecessary utilization, patients can avoid any cost at the time of care by buying private insurance to fill in the remaining 20%. A useful change in the Medicare rules would require patients who can afford it to pay that 20% out of their own pockets. There could still be a limit on the total share of income that a patient would be expected to pay, and Medicaid would continue to cover all costs for those who could not afford the cost-sharing.

The Reagan Administration should remember its stated philosophy and strengthen market incentives to preserve our private and individualistic system of health care. In this Administration dispute the Department of Health and Human Services is on the right side.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.