Shots of a Lifetime : The Drama of W. Eugene Smith’s Work Is Recaptured at the Temporary Contemporary Museum

- Share via

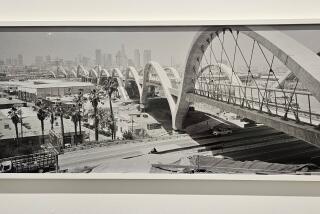

Everyone’s life is finally inexplicable; William Eugene Smith’s was rather less so. His vocation, he once said, was to do nothing less than record, by word and photograph, the human condition. No one could really succeed at such a job; yet Smith almost did. During his relatively brief and often painful life (he died in 1978 at age 59), he created images so powerful that they have altered the perception of history. (More than 250 are on display at the Temporary Contemporary through August 10.)

Until he was 25, W. Eugene Smith’s work as a magazine photographer had been remarkably consistent. It was clever, interesting, quick-witted and quick-eyed, and skilled in a narrow repertory of compositional habits. World War II would change all that. As a Navy correspondent, he was plainly shocked by the blood, madness, pain, filth and horror. He felt it first in the death of strangers--young Navy pilots burned alive--and ultimately in the death of courageous friends. He smelled the stench of war from the air while strapped into a torpedo bomber.

Characteristically, he sought to get closer to these mortal questions, to photograph on the ground, in the dirt of combat, alongside the point platoon. Despite these risks, he was always dissatisfied with himself, always looking for the perfect image that would sear the minds of the people at home.

He said: “I was after a set of pictures so that when people looked at them, they would say, ‘This is war’; that the people who were in the war would believe that I had truthfully captured what they had gone through. . . . I worked in the framework that war is horrible. I want to carry on what I have tried to do in these pictures. War is a concentrated unit in the world and these things are clearly and cleanly seen. Things like race prejudice, poverty, hatred and bigotry are sprawling things in civilian life, and not so easy to define as war.”

Smith now held a set of conscious professional values: He wanted to help humanity see itself, understand itself, cure itself. It was a goal not unmixed with his fiery ambition, partly concealed under a shy, kindly, but uneasy personality. His post-war reputation was enhanced by his affiliation with Life magazine. The photographic essay “Country Doctor” he constructed for Life was one of two that explored the subjects of birth and death in such powerful, direct and compassionate ways that he became one of the world’s greatest photojournalists.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.