Sierracin’s Tribull: Portrait of a Chairman Hit by Controversy

- Share via

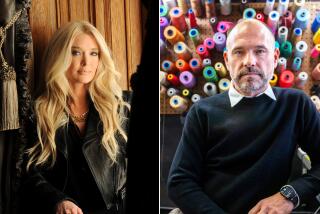

Handsome, worldly Christoph Tribull is the picture of a patrician executive with his six languages, European manners and emphasis on finance over factory floor.

But these days, the picture being drawn of Tribull is not one of elegance. The controversial chairman of Sierracin Corp. is accused in court papers of trying to depress the company’s stock so he could buy it up cheaply and plotting to sabotage the careers of those who crossed him.

Court papers also allege that Sierracin, based in Sylmar, has paid more than $100,000 to rent and maintain a house for Tribull and that he may have used company money to fly girlfriends around the world and to buy polo ponies.

Most serious, though, is the charge in civil suits that Tribull threatened to kill two of his opponents.

Tribull has declined to be interviewed in recent months, but he denied similar allegations previously. Sierracin’s lawyer, Leon Cooper, called the charges “utterly ridiculous.” Cooper and Tribull have said the accusers are either disappointed shareholders or disgruntled former officials who were dismissed.

Until he joined Sierracin, Tribull (rhymes with nibble) appeared to have a model business career. The son of a German banking executive, Tribull, 45, studied business in France. He initially followed his father into banking before serving as Dow Chemical’s financial director in Brazil from 1969 to 1974.

In 1978, Tribull bought a controlling interest in Sierracin--he now has a stake of more than 40%--and became chairman and chief executive of the aerospace and electronics company. Before long, a flood of executives and directors started to leave.

Tribull supporters say most of the allegations have come from officials whom Tribull dismissed for the company’s own good.

Walter E. Hinds, a Sierracin board member selected by Tribull five years ago, conceded, however, that Tribull could be “ruthless” in replacing executives and directors.

“He’s tough, abrasive and made some personal enemies, but I don’t think he’s hurting the company,” Hinds said.

Sierracin has had its ups and downs, but by and large it has prospered under Tribull, who blunted criticism in the past by leading the company to higher profits and strong growth.

Recently, however, Sierracin has been in a slump. Last year, it lost $2.7 million, and sales shrank 10% to $74.9 million. The company says it is in default on $8 million in bank debt. Employment is down to 1,200 from a peak of 1,550 in late 1984.

The company also is involved in legal battles with Boeing and the Internal Revenue Service that could cost millions. In addition, the company’s accounting firm qualified its 1985 audit, which means that it expressed a formal reservation about the financial statements.

Allegations in Lawsuits

Allegations against Tribull come from lawsuits filed in March by a former director, Berenice Stevenson, and in April by a former company president, Peter K. Maeussnest, both of whom say that Tribull threatened their lives.

Other questions are raised in court papers filed last year by stockholders Herbert and Euretta Hastings, whose 7% stake in Sierracin is second biggest after Tribull’s. The Hastingses are demanding access to company records to see if Tribull has abused Sierracin funds.

Similar charges have been made out of court by shareholders such as Robert A. Kelly, a Florida home builder who said he has complained to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Irving Einhorn, the SEC’s regional administrator in Los Angeles, would not comment, citing agency policy.

“It’s being run as a private company for one man,” said Kelly, who claims he lost “hundreds of thousands” on Sierracin stock but still has about 16,000 shares. “It’s his attitude that if you don’t like it, sell your stock.”

Kelly is especially incensed about Tribull’s expenses. The Stevenson suit says Tribull got $1 million in expense reimbursements from Sierracin, most of it “improper and excessive,” from 1979 through 1985. The suit says the figure was $300,000 in 1984 alone.

According to a spokesman for the firm, Sierracin last year paid Tribull through Servitec, his personal corporation, a base fee of $284,000 for his services. Tribull also received $105,368 for housing and $52,260 for tax services. That added up to $441,628. In addition, he got a car and an undisclosed sum for business travel, entertainment and other expenses that have inspired many of his critics’ complaints.

By comparison, similar companies in Sierracin’s size range paid their chief executives an average of $200,000 in salary and bonuses last year, according to a study by Sibson & Co., a leading consulting firm. Sibson also found that the only common perquisite was a company car, although some companies also offer club memberships, financial counseling and first-class air fare.

Besides accusing him of making death threats and misusing funds, Tribull’s critics say he has driven many capable executives away from Sierracin.

“People find out about him and leave,” said former President Joseph Z. Rivlin, who left the company in January, 1983.

Rivlin was not alone. According to the Stevenson suit, 17 directors, seven presidents, three vice presidents of finance and 21 division presidents left Sierracin since 1979, and Tribull’s critics say one reason is his authoritarian style.

“He runs a very militaristic business,” Rivlin said.

Maeussnest charges in court papers that he was fired as president last summer for opposing several Tribull initiatives, including a stock buyback plan intended to give Tribull as chairman a majority stake and a $1-million, interest-free loan that Tribull allegedly wanted from Sierracin.

Maeussnest, 46, who attended business school with Tribull in France, also claims in court papers that Tribull threatened to ruin him financially with crippling litigation, to destroy his career by discrediting him professionally and to harm him and his wife.

“Defendant Tribull also threatened on two occasions that he could have plaintiff killed,” Maeussnest’s suit says, in asking for $50 million in punitive damages and unspecified actual damages.

Stevenson makes similar charges, saying in court papers that Tribull threatened her life as well as Maeussnest’s and that he wanted Sierracin’s stock to go down so he could increase his control.

Stevenson, who was for a time on Sierracin’s audit committee, also questioned Tribull’s expenses, although she acknowledges that she did so after learning that she would be dropped from the board in May, 1985. In January, Tribull and Sierracin sued Stevenson for defamation, breach of contract, fraud and other complaints, prompting her countersuit in March.

Feuds for 8 Years

The complaints against Tribull reflect the feuds that he has had with dissidents during the nearly eight years since he took control of Sierracin, whose products include aircraft cockpit windows and a plastic substitute for bulletproof glass.

It also makes motors, heaters and electronic components. Aerospace accounts for 52% of sales and is generally its most profitable business. Industrial products contribute 28% of sales, and 20% is from electronics.

A large hunk of Sierracin’s 1985 loss is a $1-million after-tax charge stemming from a jury finding that Sierracin used Boeing designs to make cockpit windows for other manufacturers. Sierracin is appealing the decision.

Sierracin also is fighting the IRS in U.S. Tax Court over an accounting method that it and many other aerospace firms use. Sierracin says that if it loses, it will have to pay $1.8 million in deferred taxes, plus $2.3 million in interest.

The Hastingses complain in court documents, meanwhile, that Sierracin made unexplained cash advances to Tribull of $52,500 in 1983 and $154,503 in 1984, the latter including individual advances of $74,003 and $30,000. They charge that the $30,000 was used to purchase polo ponies, a claim specifically denied by Cooper, the attorney, and by the audit committee of Sierracin’s board.

The Hastingses also complained that the company has balked at showing how the cash was spent or whether it was paid back by Tribull.

In court papers, they say Sierracin also paid:

- Roughly $12,500 for Tribull’s polo-playing fees.

- $1,914 in air fare plus other expenses for Miguel Bouradieu to visit Southern California twice from Ezeiza, Argentina. The Hastingses contend that Bouradieu was apparently the trainer of Tribull’s polo ponies.

- Thousands of dollars in expenses for women whom the court papers call Tribull’s girlfriends, including $100 bouquets and “nearly $7,000 of airplane tickets for his girlfriend, Christina Magnusson, to join him in Paris, and to fly to Hawaii and Copenhagen.” The Hastingses’ papers say Tribull may have paid Sierracin belatedly for the airplane tickets.

Responding to a recent study by Sierracin’s audit committee, Tribull agreed to reimburse the company for $131,000 in personal expenses that a company spokesman acknowledges were not proven business expenses. The committee, however, cleared Tribull of any possible wrongdoing.

Gary Patten, Sierracin’s vice president for finance, said the $131,000 represented expenses that were not fully “documented” as business expenses--such as a florist’s bill--or stemmed from “accounting errors” by Sierracin. He said the company had underestimated the amount of money that Tribull owed it for personal expenses in 1981 and 1982 and never reconciled the difference.

In interviews last year, Tribull brushed aside criticism from his opponents.

“If the allegations were true, I’d confront them,” he said in lightly accented English. “But the allegations aren’t true.”

Tribull said he ousted many executives and directors because a housecleaning was needed when he took over the company.

“Management was weak,” Tribull said. “They hadn’t grown for over a decade, but they had a clean balance sheet and good technologies.”

Sierracin earned profits under Tribull for several years. Earnings climbed to $4.5 million in 1984 from $1.5 million in 1978, while sales rose to $83.5 million in 1984 from $26.5 million in 1978.

But the climb has not been steady. Besides last year’s $2.7-million deficit, Sierracin lost $1.1 million in 1981.

Tribull supporters say the company’s recent setbacks inspired Tribull’s opponents, particularly Maeussnest, Stevenson and the Hastingses, to challenge him.

“You’ll probably find they collaborated to get rid of a guy they don’t like very much,” Hinds said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.