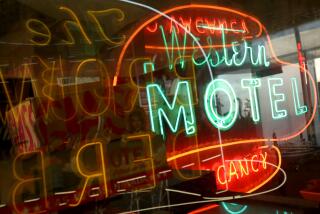

What’s New in Neon : Artists Have Demanded New Glasses, New Gases, New Colors. Now the Medium Has More to Say Than ‘Eat at Joe’s’

- Share via

Ten years ago, neon--a medium associated with both the highest aspirations and lowest commercialism of the American Dream--was dying. But, as neon artist Richard Jenkins once said to me, artists have brought neon down off two-story buildings and into people’s living rooms. Neon has become a vital art form with a potential that has only begun to be tapped. And I think the medium has been resurrected because artists have taken hold of it and insisted on information and materials.

When I first began working in neon in 1966, only two gases were used in commercial sign production: neon, the bright-orange gas that gave the whole medium its name, and argon, a pale-lavender gas that’s often combined with mercury to become light blue. Commercial sign makers still use only those two, but artists have created a demand for two other gases: helium, which is flesh-colored, and krypton, a silvery-white gas.

It was only after Jenkins and I started teaching large numbers of artists and they started asking for different colors of glass tubes that some essential colors became available. Corning had stopped making red, yellow and blue tubes. It’s amazing to think of an artist not being able to get red, yellow and blue glass. Now you can get those colors again, as well as a new emerald green. When Rudi Stern wrote “Let There Be Neon” in 1979, only 15 colors were possible in neon art. But now, depending on the kind of gas, the glass tube containing it and the phosphor coating the inside of the tube, we can make 150 colors of neon--because artists wanted access to those colors.

The technology of neon--capturing in a glass tube an inert gas that glows when electrified--is basically the same as at the time of its invention, with one exception: the addition of computer animation. A lot of neon animation is still done the old way--motors with cams controlling when the neon elements go on and off. But now, changing the elements is as easy as punching out a different computer program. I recently completed a neon installation in the Loews Anatole Hotel in Dallas; it’s an 80-foot mural of flamingos, birds of paradise and leaves suspended over a disco dance floor. The flamingos and leaves are made up of abstract lines; computer animation allows you to play with the lines in endless combinations. The disc jockey at the light board can change the arrangement instantly, while playing records.

Until the 1960s, neon was used only for signs. Now, artists use it for sculpture, in two-dimensional pieces, as architectural decoration and as illumination. In Los Angeles, for example, we have such artists as Norman Grochowski, who embeds neon tubes in big carved rocks; Larry Albright, who makes globes containing lightning-like fields of colored light and sets them on top of cabinets for a mad-scientist look; Eric Zimmerman, who uses computer-animated neon combined with mirrors and chrome, and Michael Hayden, who made the large computer-animated rainbow at Pershing Square.

There’s activity elsewhere too. Brian Coleman of Santa Cruz makes organically shaped fusions of colored blown glass that he hangs from the ceiling, and Victoria Z. Rivers of Sacramento paints over white neon tubes set onto batik-like silk “canvases.” One of the first people to take neon out of the commercial-sign context was Chryssa, who came to New York from Greece in the early ‘60s and was captivated by the signs in Times Square. She makes plexiglass-and-metal boxes containing rows of abstracted letter forms. New Yorker Stephen Antonakos has made large geometric shapes that are attached to buildings. And one of my favorite artists, William Shipman of Kansas City, salvages scraps of neon tubing, puts them inside an embryonic-looking fiberglass structure, then sets the whole thing in an old chair. They look like glowing mummies; they have a wonderfully raw, emotional quality.

I’m happy to see that public acceptance of neon as art is becoming more and more widespread. Neon shows up frequently in rock videos; it’s in promotional logos for television shows. It’s becoming the look of the ‘80s.

The Museum of Neon Art is limited by space and money, but it’s still the only one in the world and has attracted thousands of visitors. I envision it becoming large and elaborate; ultimately, I would like to see it as a kind of neon Disneyland. The public loves Disneyland; it’s art you can ride and interact with. I think that should happen to neon art.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.