Perle Wages Behind-the-Scenes Crusade Against Kremlin : Soviets’ Mortal Foe Lurks at Pentagon

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The wise men of U.S. foreign policy, upon hearing that Soviet soldiers had briefly held a U.S. military team in East Germany at gunpoint in early September, were in agreement: In the interest of cooling the angry rhetoric between East and West as the Reagan-Gorbachev summit meeting approached, they would not draw attention to the incident.

For eight days, the secret was kept. On the ninth--an otherwise quiet Sunday in Washington--it burst into the open when Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger was asked about it on the CBS News program “Face the Nation.”

How did the secret leak? One person was responsible: Richard N. Perle.

Apprehensive that the climate between the superpowers might grow too mild before the summit, Perle, assistant defense secretary for international security policy, had dinner the night before Weinberger’s appearance with “Face the Nation” host Lesley Stahl.

Primed by Perle, Stahl asked Weinberger about the incident on live network television, and the secretary, as Perle had anticipated, spilled the details. Expressing a long-held view he shares with Perle, the secretary said: “You just have to recognize that this is Soviet behavior.”

It may have been Weinberger talking, but it was a vintage Perle performance, a case study in the maneuvering and manipulating that have put Perle, in the words of one of his admirers, into “the bureaucratic hall of fame.”

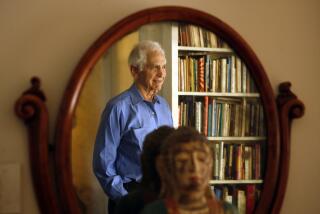

Prince of Darkness to his enemies, Sir Galahad to his allies, Richard Norman Perle has colored U.S. foreign relations for a decade and a half with his deep, dark suspicion of the Soviet Union. A Senate aide for nearly a decade and a high-ranking Defense Department official for the last five years, the 44-year-old Perle has become the eminence grise behind all things anti-Soviet in the government.

He draws on an arsenal of assets--a sharp, analytical mind, unflagging energy and bureaucratic finesse buttressed by the allies he has carefully placed throughout the foreign policy agencies of the government--to wield extraordinary power on such central issues as arms control. His ideological kinship with Weinberger and the confidence that he has Weinberger’s complete support have conferred power beyond his third-level position in the Pentagon.

Here comes Richard Perle, 5-feet-10, 190 pounds, unathletic and obviously well fed. Although it is barely noon, his finely tailored British suit is already rumpled, and he is showing a five o’clock shadow. He is ambling out of the glare of seven television lights after an easygoing performance before a friendly Senate subcommittee, where he issued yet another reminder that the Soviets are out to beg, borrow or steal America’s high-technology secrets.

Here is Richard Perle picking at sugary French toast at a breakfast with a group of Washington reporters, complaining that the latest Soviet arms control proposal provides no grounds for agreement. “It is hopelessly self-serving and one-sided.”

And here is Perle ordering up new Pentagon research on the 1972 anti-ballistic missile treaty and the record of the negotiations that produced it. That assignment helped provide the reinterpretation of the treaty in a light that would not hamper work on Reagan’s “Star Wars” program of space-based anti-missile defenses.

Lengthy Vacations

But there is another Perle, the one who retreats to a country house in the South of France for about five weeks each summer on a holiday whose length sets him apart from his colleagues.

This is the Perle who provides for the special needs of his brain-damaged younger brother and his divorced first wife. It is the Perle who takes into his home a puppy--a mutt resembling a German shepherd--that has planted itself on his suburban doorstep in a snowstorm.

And it is the Perle who slips a quotation from a William Butler Yeats poem--”Move most gently, if move you must”--into an arms control memo. “The level of literacy in the bureaucracy is just astonishingly low,” he said, chuckling at this private crusade.

Driving Perle is a view of the Soviet Union as a place of Orwellian totalitarianism where--and here he steals a line from George Orwell--”yesterday’s weather can be changed by decree.”

“They want a world in which no decision can be taken anywhere that isn’t consistent with Moscow’s interests,” he said. “We, by contrast, are quite happy with a world in which we are free to pursue our constitutional defined role of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness without outside interference.”

To Weinberger, Perle’s consistency is an asset. In an interview, the secretary said Perle “has a philosophical rudder that guides him. He doesn’t swing around from position to position trying to be on the winning side.”

That philosophy, as a former colleague explained, allows Perle to “make demands on the Soviets that are so radical that they have no chance of being accepted, and then, when the Soviets turn down such reductions, he says, ‘I told you they weren’t serious, and what we need is hard-nosed competition.’ ”

‘He’s Dr. No’

Or, as a Senate aide said: “Richard is very effective at being negative. He’s the Dr. No of this Administration. He’s never met an arms control treaty he liked, and he never hopes to meet one.”

This source described Perle disapprovingly as “a hard, right-wing conservative.” But he also called him “very bright. Extremely nice guy. Pleasant, very pleasant. Articulate. Friendly, very friendly.”

His calm, even manner in public turns icy in private debates on East-West issues as others around him heat up. In the view of one national security expert who has done battle with Perle over the years, “there is a side to him that just has a fury” when the issue is the Soviet Union.

But Walter B. Slocombe, a deputy defense undersecretary under President Jimmy Carter and one of the few people associated with Perle willing to discuss him on the record, said “he isn’t obsessed” with the dark side of the Soviet Union. “If you ask him about the SS-25 (a new Soviet missile), he’ll be interested in the subject. But you can talk for hours and hours without ever talking about these issues.”

Perle, a complex figure who in fits of pique says he would like to chuck it all and open a souffle restaurant, has been around.

Perle’s influence can be seen in the limits imposed by the Senate in 1972 on future arms control treaties; the Senate’s failure to ratify SALT II; 1974 legislation tying favorable trade treatment for the Soviet Union to the freedom of Jews to emigrate; the deployment of medium-range Pershing 2 and cruise missiles in Europe in 1983, and now the overall cast of U.S.-Soviet relations.

Key Opposition Role

During the aborted arms control talks of the first Reagan Administration, experts say, Perle played a key--if not deciding--role in the Administration’s opposition to the “Walk in the Woods” proposal developed informally by the chief U.S. and Soviet negotiators in talks on intermediate-range nuclear weapons.

The plan would have sacrificed the Pershing 2s in exchange for limits on Soviet SS-20 missiles, but Perle, distrusting Soviet intentions, prepared a report for Weinberger that helped lay the groundwork for U.S. objections.

On the recent reinterpretation of the 1972 ABM Treaty to permit “Star Wars” research, Perle worked “with great gusto . . . assiduously . . . talking to people, and, in particular, he assured that the legal analysis got into the right hands,” said one person who observed his work.

“He assessed where the choke points were--the key individuals who had to be influenced and brought along at senior levels of government. Sure enough, in a very methodical fashion, he built alliances and pushed the issue to the point it was addressed and agreed upon.”

Or take the case of the American-made VAX 11/782 computer that was seized by West German authorities in Hamburg in November, 1983, seven minutes before it was to be shipped to the Soviet Union.

Smoking Gun

It represented the smoking gun Perle needed to prove that technology with potential military uses was leaking to the East. And it enabled him to win a running feud with the Commerce Department, which had traditionally supported industry in its quest for fewer export controls.

“He’s the first defense official who has ever been really effective in prodding the Administration to do something about choking off the drain of technology,” said a longtime observer of the Pentagon. Perle, who regards the issue as second in importance only to arms control, ultimately gained an Administration policy of tighter controls of high-tech exports.

So, when the computer’s retrieval was announced, Perle “leveled the Commerce Department” in his public statements, one Pentagon official said, prompting Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldrige to ask Weinberger in a letter to fire Perle. Weinberger dismissed the suggestion.

Perle’s interest in the complex world of superpower relations and the nuclear arms race began not with a bang but with a splash. As Perle recalled, it was 1959, his senior year at Hollywood High School in Los Angeles, two years after Sputnik, when Joan Wohlstetter, a classmate, “invited me over to go swimming one day and introduced me to her father, and we fell into a conversation.”

Albert Wohlstetter, then an economics professor at UCLA, gave Perle a copy of his just-published essay, “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” a watershed article in Foreign Affairs magazine that helped chart a new, hard-line course in the world of strategic thinking. Awakened to a new subject, Perle ultimately shifted his major at USC from English to international relations.

Perle interrupted his studies at USC to spend the 1962-63 academic year at the London School of Economics. His roommate was Edward N. Luttwak, who is now a military analyst and author of “The Pentagon and the Art of War.”

Anti-American Demonstrations

When the Cuban missile crisis erupted, so did the London campus in what Luttwak called “an orgy of anti-American demonstrations.” In the main assembly room of the Old Theatre, “speaker after speaker rose up to denounce the (John F.) Kennedy Administration and the United States and to defend the Soviet Union,” Luttwak said.

Along came Richard Perle. As Luttwak tells it: “He got on the stage and soberly pointed out there was a meaning to the balance of power and any abrupt attempt to change the nuclear balance by sneaking short-range weapons into Cuba was the nuclear equivalent of a covert preparation for a surprise attack, and the United States had to reply. By the way he said it, he transformed the mood of that entire vast hall and made an indelible impact on all who heard him.”

Perle later received a master’s degree in international studies from Princeton University, but he dropped out before completing his doctoral thesis on international negotiating styles.

Landing in Washington in 1969, as Richard M. Nixon and Henry A. Kissinger were turning toward detente with the Soviet Union, he took a job on the staff of Sen. Henry M. Jackson (D-Wash.).

“He learned at the knee of a very powerful senator how to get things done,” recalled a Senate aide who worked with him. “He took his native intelligence and combined it with a very soft-spoken public style of sweet reasonableness. He’d come up with one or two arguments that were hardest to answer, and keep pressing them.”

Gathering experience far beyond that of his bureaucratic adversaries in today’s Reagan Administration, Perle quickly established a close relationship with Pentagon officials working on the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. He and the senator failed to derail SALT I, but they managed, through sharp questioning in hearings and persuasive conversations with colleagues, to put the Senate on record demanding that any subsequent accord require equal weapons levels on both sides.

‘Totally Wired’

When negotiations began almost immediately on SALT II, Perle was in a better position to influence the outcome. “Richard was totally wired to the Pentagon,” said one arms control expert who served on the staff of the National Security Council.

The result: Classified information about the U.S. negotiating position began circulating around Washington, undermining the negotiators and drumming up opposition to the treaty, which Perle, Weinberger and Reagan considered “fatally flawed” even before it was completed in 1979.

In his years in Washington, Perle has developed a reputation for manipulating his bosses, first Jackson and then Weinberger. Perle strongly dissents.

“It has been largely the other way around,” he insisted. “I was a 27-year-old graduate student when I went to work for Scoop Jackson, and anybody who knew Scoop would consider it laughable that I was an influence on him rather than the other way around, which is the fact.”

Well-placed arms control experts say he gained a much deeper grasp than Jackson of the details of strategic weaponry. But it was Jackson, a Scandinavian Protestant, who interested Perle in Israel, awakening in that grandson of Russian Jewish emigrants an interest in Judaism and Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union.

As for Weinberger, an official who served in the Pentagon during the Carter Administration said: “Cap Weinberger speaks with Richard’s voice.”

One day in 1983, for example, a high-level Pentagon board was considering, without signs of objection, an Army plan to withdraw 20,000 troops from Europe in a budget-cutting move.

Arguing that such a step would send a wrong signal to the Soviets in the midst of negotiations over the superpowers’ nuclear arsenals in Europe, Perle, according to one participant, turned the decision around. Crucial to Perle’s success, this source said, was the recognition by the other Defense Department heavyweights that when Perle spoke, Weinberger would listen.

Different Work Habits

It is not Perle’s work habits that ingratiate him with his boss. In the meticulous and regimented Pentagon, Perle is famous for skipping most early-morning meetings of the senior Defense Department staff; for being unceremoniously thrown off the Defense Resources Board because he avoided its meetings and displayed what one former colleague called “a cavalier disregard for the making of the defense budget;” for traveling without telling Weinberger of his plans, and for letting important reports go untouched in his briefcase for weeks at a time.

But Weinberger seems not to mind. “I have never felt it particularly useful to have everybody all regimented into the same desk, the same uniform, the same hours and all the rest,” the secretary said. “He gets very good results. He has different methods of working than I do or others do, but the results are what count . . . He’s a very valuable, valued adviser.”

Perle has plenty of allies around town besides Weinberger. They are scattered in powerful positions, many that he found for them: on the arms negotiating team in Geneva, in the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, on the National Security Council staff and in other Pentagon offices. “He’s a virtual one-man hiring hall,” said a former arms control negotiator.

And when columnist George Will gave a dinner at his home for Perle last summer, one of those in attendance was the President of the United States.

Finally, here is Richard Perle with his 6-year-old son. Jonathan Perle can assemble a jigsaw puzzle map of the world and identify the nations. But when he reaches the Soviet Union, he simply says, “The bad guys.”

At home, Perle shares with his second wife, Leslie, a U.S. Customs Service economist, the chore of putting Jonathan to bed. It’s a losing battle--Jonathan is as intractable as any Soviet arms negotiator--but Perle has tried a method learned from an Army brigadier general who bribed his children with nickels and dimes.

The Perle household--he earns about $72,000 a year and her salary is about $65,000--should be able to afford nickels and dimes. But when the new regime in the Perle household was one month old, the Prince of Darkness, that notorious hard-liner and master of manipulating the bureaucracy, was asked if it was working. His reply: Jonathan is up to $20.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.