Beating the Drums for Witchcraft : Berkeley Chemist Validates Jungle Wisdom in His Lab

- Share via

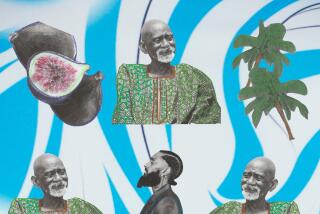

BERKELEY — Annually, Isao Kubo leaves his tiny, crowded laboratory in the basement of Wellman Hall at UC Berkeley and flies to Africa or South America to chat with witch doctors.

Those chats lead Kubo on collection trips up tall trees, through murky waters and into the soil, all for the sake of humankind. Then they lead him back to Berkeley, hauling shrubs, roots, leaves, fruits and oils used in underdeveloped countries to cure ills ranging from headaches to cholera.

At home, the 47-year-old chemist and five assistants employ a jumble of what Kubo calls “very expensive toys” in a lab so jammed with furniture and equipment that you have to turn sideways to get past some of it. The place looks like Frankenstein’s laboratory with a little Houston Mission Control thrown in. Seven more assistants work in a less-crowded room across campus.

After sequences of distilling, gurgling, calculating and checking of digital readouts, Kubo finally knows--chemically speaking--exactly what he’s brought home. Having broken the folk remedies into their chemical components, the professor goes after the active chemicals, the ones that make the remedies work.

No Takers So Far

Then he synthesizes those active chemicals and, presto, the witch doctors’ jungle wisdom has been re-created in a Berkeley laboratory.

When he believes he has successfully synthesized a usable medication, Kubo tries to persuade a pharmaceutical company to manufacture and distribute the drug.

So far, no company has been convinced. But, Kubo said, for five years a major drug company has been testing a potential remedy for cholera. Kubo developed the remedy from maesanin, a chemical he extracted from East African shrubs after watching entire tribes line up to drink tea made from the bush in an effort to ward off cholera. “It takes an average of 10 years for a pharmaceutical company to do the tests,” Kubo explained.

Although he has not yet been able to market them, Kubo cited numerous African remedies that may have medical application the world over. He speaks of a headache and memory aid drug taken from the bark of an African tree, a drug from a South American tree used for treating kidney problems and a compound from the bark of a tree in the Amazon that healers prescribe for a disease caused by flukes, a parasitic worm.

The chemist said several companies are considering selling compounds he derived from African plants that “significantly increase the antibiotic effects of certain commercial drugs.”

Kubo pointed out that new antibiotics are always needed because organisms become immune to existing medicines. The professor hopes to find some of those needed antibiotics in nature.

Medicine men are psychiatrists as well as internists, so Kubo can’t use every treatment they prescribe. “Many times information I get from the witch doctors seems to indicate just psychological effect. I cannot prove any chemical effect,” he said.

There is nothing new about deriving drugs from natural sources. Kubo observed that quinine can be made from the bark of the cinchona tree in Asia and Africa, synthetic codeine chemically duplicates the codeine found in opium poppies, ipecac can be made from the root of a Central American plant. And, he adds, 18th-Century English heart patients were apparently the first to be treated with medicine made from the leaves of the foxglove plant, the active ingredient of which is digitalis.

Pesticides the Natural Way

When Kubo is not working on medicine to keep people alive, he is working on pesticides to kill bugs. He has discovered natural pesticides by watching Africans dump certain shrubs into ponds to rid the water of pests, and by noting that locusts in Kenya strip the landscape of vegetation except for a kind of grass that contains a natural insecticide.

Unlike many artificial pesticides, which linger for decades, pesticides developed from nature are biodegradable. Also, Kubo said, most commercial pesticides work by attacking the nervous system, and the poison doesn’t care whether that system belongs to a bug or a person. Most natural pesticides are harmless to humans, Kubo added, because natural pesticides tend to interfere with an “insect specific” process, such as the way an insect reproduces, matures or finds food.

For example, Kubo has found that anacardic acid in the root bark of the African msimbwi tree can prevent cricket reproduction. Experiments are under way to see if the acid also will stop reproduction in cockroaches, which are close relatives of crickets. Those experiments began after the professor noticed Africans dumping the fruit of the cashew tree into ponds to kill mosquito larvae and aquatic snails. He later found that the active ingredient in cashew fruit and msimbwi tree root bark was the same.

In East Africa, the chemist found that a mixture of two chemicals from the podocarpus tree (found in many locations, including California) promotes growth in young rice plants but inhibits the growth of lettuce, which is related to many weeds.

Most Bizarre Work

Kubo also is working with chemicals from olive fruit, seeds and leaves that repel both pink bollworms, which attack cotton, and fall armyworms, which devour cotton and corn. Chemicals from citrus fruit and seeds also act as pesticides on those worms and other pests, the scientist said.

The professor’s most bizarre work stemmed from his observation that locusts in East Africa stripped the land of vegetation except for an annual grass called Ajuga remota . He subsequently fed pink bollworms and fall armyworms a compound extracted from the leaves and roots of the grass. As a result, the worms not only failed to shed their helmet-like moltings, but grew extra ones that prevented them from eating, so they starved to death.

“We have to learn from nature,” Kubo said, “because Mother Nature has learned how to control pests and weeds. We have to learn how to do it from nature.”

Kubo might not be hobnobbing with witch doctors if his mother had not developed a uterine ulcer when he was a high school student in Osaka, Japan’s second biggest city.

“There was not good medicine available,” Kubo said. “What there was gave my mother bad side effects. So I thought, ‘Someone has to do some kind of research to look for new medicines.’ ” Kubo decided to be the one.

The teen-ager had been preparing for a career in commercial art at an arts and crafts high school. Only about 3% of its students went to college, and almost all of them studied art, he said. They were prepared for nothing else. So Kubo took a year off after high school and “studied night and day” to teach himself math, science and English. He also worked, tutoring junior high school students.

By 1969 Kubo had a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Osaka City University and a job at the University of Rochester in New York. At Rochester, he used easily available chemicals to synthesize camptothecine, a compound isolated from the bark of a Chinese plant not available in this country.

Kubo said the compound arrested tumors in mice, and had an impressive theoretical application in human medicine . . . except for one problem. The drug’s side effect was brain damage. The National Institutes of Health, which had been bankrolling Kubo’s project, decided exchanging tumors for brain damage wasn’t a good trade-off and dropped their support, the professor said.

After two years at Rochester, Kubo went to the University of Oklahoma to study marine natural products for a year.

“He did excellent work,” said Francis J. Schmitz, under whom Kubo studied. “He is an extraordinary person, an extremely capable, energetic and dynamic person. When he was here he was a very accomplished chemist in terms of isolating and determining the structure of organic compounds,” commented Schmitz, who still teaches at the university, in Norman, Okla.

In 1972, Kubo left Norman to return to Osaka City University where he taught for two years. Then the Japanese government sent him to Nairobi to the International Center of Insect Physiology and Ecology. His assignment: synthesize a chemical used by insects for communication.

Insufficient Facilities

In Africa, Kubo said he found insufficient facilities, had a terrible time getting supplies and constantly got tangled in governmental red tape. He couldn’t get his work done.

“I was very frustrated. I had to do something. So I started going into the jungle to see bwana mganga (witch doctors, medicine men). In the beginning I couldn’t get anything. But I kept going back, and the witch doctors started talking to me.”

For two years Kubo, who speaks Swahili, bounced through Kenya and Tanzania in his Land Rover, talking with bwana mganga. He collected 250 plants which, among other things, reputedly cured stomach aches, malaria, headaches, diarrhea and cholera.

In late 1975 Kubo took his plants and his knowledge to Columbia University in New York. After four years at Columbia researching natural products, he moved to Berkeley where he continues working for healthier people and fewer bugs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.