In the NBA, East Always Pushes West Around

- Share via

James Naismith no doubt did a few quick Michael Jackson-type spins in his grave when the Chicago Bulls beat the Milwaukee Bucks recently and Chicago Coach Kevin Loughery said: “This is the way an NBA game’s supposed to be played--bodies flying all over the place, elbows and arms extended and everybody fighting to get his hands on the ball.”

That could also serve as the description of a successful Super Bowl, or, without the part about the ball, of a scintillating Roller Derby match.

It’s also a good definition of Eastern-style basketball, at least in the NBA. The Lakers found out about that last year in the NBA championship series against the Boston Celtics. In that particular series, nice guys finished last.

What’s the story on East vs. West? For an expert analysis, I called upon Junior Bridgeman of the Los Angeles Clippers. Before being traded to the Clippers this season, Bridgeman played nine seasons for the Milwaukee Bucks, an Eastern team coached by a former Celtic, a non-finesse player named Don Nelson.

I asked Bridgeman, a former law student possessing a keen, analytical mind, to compare Eastern and Western styles of hoops.

“The West is definitely more finesse-type basketball,” Bridgeman said. “It’s more of an open game, a little less contact. It seems to me the Eastern teams concentrate a little more on taking away what teams like to do.

“Doing that, you’re going to have to play guys a little more physical, not allowing guys to get where they want to be on the floor. It’s just a little different philosophy.

“All these teams (in the East) just seem to be a little bit more physical, there’s a little more hand contact, a lot more pushing around the basket than what I’ve experienced in half a season in the West.”

Ironically, Bridgeman is a finesse-type player who thrived in the East. He is considered one of the most valuable sixth men in the NBA, instant offense, but more of a darter than a banger. His trademark is durability and consistency.

Not counting his rookie season, Bridgeman has never averaged fewer than 12.5 points a season, and never more than 17.6. His career scoring average is 14.4 and this season it’s around 14.6. He has missed an average of only six games a season.

In high school, along with basketball, Bridgeman played the clarinet and the saxophone, and played ‘em well. He understands that playing basketball on the highest level is like making beautiful music, a symphony of touch and teamwork, not a street fight.

He plays the game his way, but he realizes that some contact is entertaining to the fans, and he understands the need for muscle.

“We (the Bucks) were a young team (early in his career at Milwaukee) and a lot of guys had been used to playing a finesse game,” Bridgeman said. “We probably had a reputation of just being too nice. Yeah. We’d play hard, but by the rules, and wind up on the short end of the stick a lot of times.

“He (Nelson) used to say that in this league, if you come out and play aggressively, it seems you’re the team that gets all the calls, all the breaks. It’s like the officials get used to seeing you play that way and now they let that go. Teams that try and counter what you’re doing and aren’t used to playing that way, they start to look more flagrant and they get the calls against them.”

So it’s important to be tough. But when does admirable aggression cross over that thin line and become criminal thuggery?

“Being in the league a long time, you know when guys start to cross the line from playing physical to playing downright dirty,” Bridgeman said. “There are certain guys who have a reputation for crossing the line. . . . There are a few cheap-shot type guys.”

He didn’t care to mention any of them, of course. But what about the noncriminal tough guys?

“You have to look at Dennis Johnson (Celtics), Michael Cooper (Lakers), Sidney Moncrief (Bucks), Maurice Lucas (Suns). A lot of people seem to think sometimes he (Lucas) crosses the line, I’m not sure. The power forward is the most physical position, the one where they cross the line pretty easily.

“(Larry) Bird is physical, all of Boston--(Cedric) Maxwell, (Kevin) McHale, all those guys, that’s the way they play. Buck Williams (New Jersey). Rick Mahorn (Washington) definitely has to go on the list as being one of the guys. He can play right around the edge, and can cross over very easily, depending on how things are going.”

What about other tough-guy players on the West Coast?

“Around the West?” he said. “Let’s see . . . “

Long pause.

“I can’t really think of any.”

Why is that? Maybe it’s the weather. Hard winters seem to make people a little tougher, a little grouchier than the folks who can sit on the beach in late January.

Maybe it’s the sociological climate. Fans out West tend to be less vocal, less vigorous than their eastern counterparts. Maybe that aggression rubs off on the players.

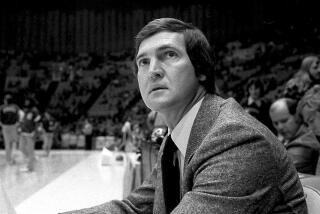

Maybe it’s the coaches. Nelson, Loughery, K.C. Jones of Boston, and Billy Cunningham of Philadelphia are all former Eastern players, raised on sharp elbows and crunching hand checks.

Whatever the reason, bullyball seems to be the rage, the current formula for winning games. The Lakers, for instance, were on a hot streak, went East, got pushed around and dropped three straight games.

You’ve got to muscle up these days. Even a finesse guy like Junior Bridgeman can see that.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.