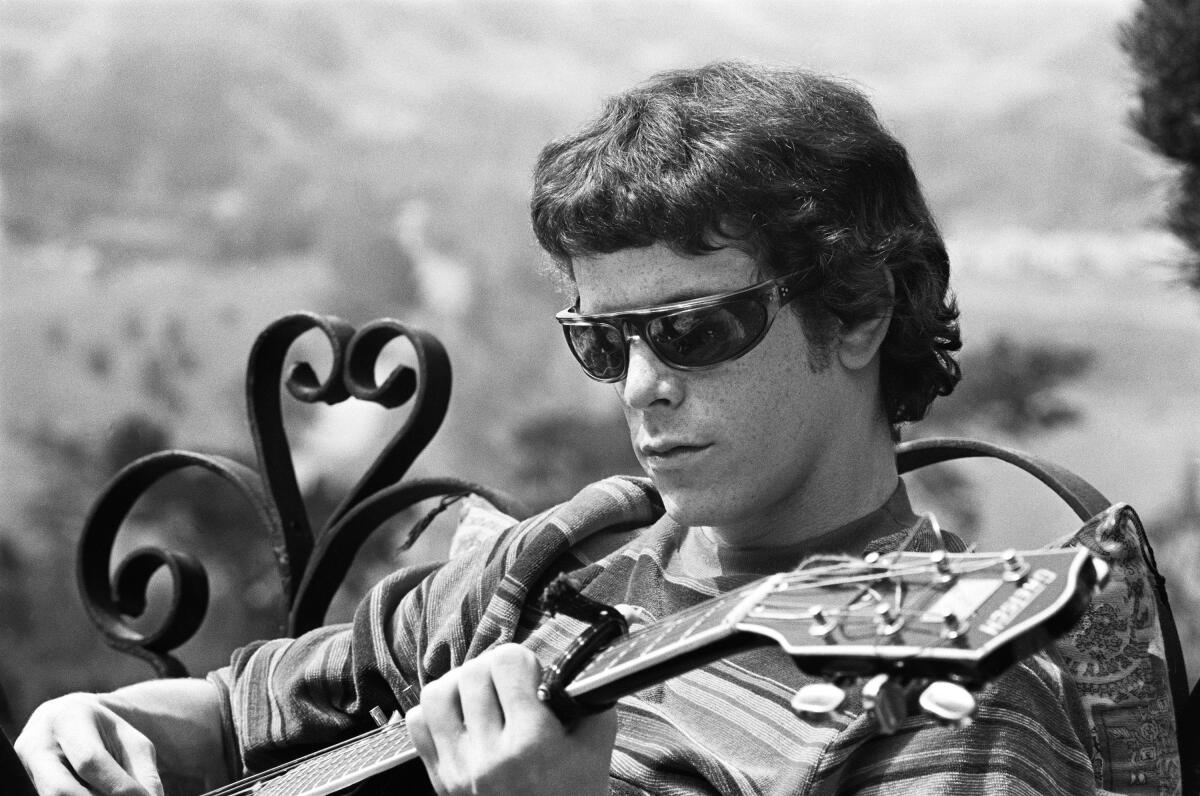

A Word, Please: Did AI generate a post listing Lou Reed’s best songs?

Recently, author Neil Gaiman posted on Mastodon a link to a blog titled “The 20 Best Lou Reed Songs of All Time” with this comment: “the first time I’ve read an article that I could swear was generated by AI. Whenever it actually describes the lyrical content of a song it’s either slightly wrong, very wrong, or so generalized as to be possibly talking about any possible song.”

I don’t know much about music, but I know a little about writing, so I was curious whether the form was as revealing as the substance. It was.

Here are the first two sentences about song No. 10: “How Do You Think It Feels” is a track from Lou Reed’s 1973 album “Berlin.” The song is a haunting ballad that explores themes of heartbreak, loneliness and despair.

Now song No. 11: “Disco Mystic” is a track from Lou Reed’s 1979 album “The Bells.” The song is a funky, upbeat track that features a driving bassline and infectious rhythm.

No. 12: “Ennui” is a track from Lou Reed’s 1974 album “Sally Can’t Dance.” The song is a laid-back, jazzy track that features a smooth saxophone solo and Reed’s trademark deadpan vocals.

No. 13: “Kicks” is a track from Lou Reed’s 1976 album “Coney Island Baby.” The song is a fast-paced, guitar-driven track that showcases Reed’s trademark snarling vocals.

I don’t know whether this unbylined blog was written by a computer or by a cat walking on a keyboard. But a human writer seems unlikely. In all my years of editing writers good and bad, I’ve never seen anyone use identical sentence structures on repeat. For every entry, the first sentence had as its subject either the song title, the words “the song” or a synonym, all followed by “is” then another synonym for “song,” often “track.” Then they repeat Lou Reed’s full name, followed by a year, followed by an album title.

At their heart, all 20 first sentences say, “The song is a song.”

Often, the next sentence said the same thing. For example, the second sentence in No. 11 was: “The song is a funky, upbeat track,” aka “song.”

Not good.

Main clauses are prime real estate in a sentence. You shouldn’t squander them on self-evident statements like “the song is a song.”

Some of the hollow statements in the blog post piled on extra redundancies: “The Bells” is the title track of Lou Reed’s 1979 album of the same name.

Readers expect the first noun after a modifying phrase to be the person or thing the phrase applies to, but a lot of sentences put that information elsewhere.

You don’t have to say the album has the same name as the title track, since that’s what “title track” means.

Two sentences in the piece say a song was “released as a track” on an album. Another waste of readers’ time.

Humans who write well don’t do this. Instead, they avoid empty statements and they make their main clause interesting and their verb substantive.

Consider this sentence from Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: The holy mother of all diss tracks, “You’re So Vain” contains one of the most enduring musical mysteries of all time.

It sounds like a human wrote it. And even when you set aside the strong, engaging voice, you can see that the structure of the sentence is strong, too. There’s an introductory phrase — a great way to avoid monotonous subject-verb starts to every sentence — followed by a main clause built on a verb other than “is.”

Another first sentence in the Rolling Stone list: “Purple Haze” launched not one but two revolutions.

Another: The Stones’ experimental mid-Sixties period was partly driven by Brian Jones’ restlessness.

Another: Embroiled in a love triangle with George and Pattie Boyd Harrison, Clapton took the title for his greatest song from the Persian love story “Layla and Majnun.”

Another: The keynote from Bowie’s 1971 album, “Hunky Dory,” “Changes” challenged rock audiences to “turn and face the strange.”

Notice the verbs: They’re dynamic and engaging — launched, driven, took, challenged. Notice the subjects: They’re not all the title of the song or the words “the song.” Notice the variation in sentence structure: Some sentences use introductory phrases before the main clause to stave off monotony. Notice the substance: The multiple Rolling Stone writers who contributed to this compilation all had interesting facts or observations to share.

Will AI programs ever master this human touch? Probably. But whatever or whoever wrote this Lou Reed piece hasn’t nailed it yet.

June Casagrande is the author of “The Joy of Syntax: A Simple Guide to All the Grammar You Know You Should Know.” She can be reached at [email protected].

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.