Apodaca: An early desegregation battle fought in Orange County exemplifies the importance of ethnic studies

Several months ago I attended a comedy show. I was still shying away from large gatherings, but this event was outdoors and a friend was performing. I figured I could use a few laughs.

But one of the other performers had a serious question. She asked if anyone had heard of the Mendez case.

In an audience of maybe 40 people, a single hand raised — mine. The performer seemed a bit surprised that even one person was aware of it.

And this is exactly why we must do better at teaching history.

Lately we’ve been subjected to widespread disinformation and discord over the introduction of ethnic studies and other attempts to provide schoolchildren a broader, deeper, more diverse perspective on history. Critics bandy about terms like “critical race theory” and insinuate that kids are pawns in a damaging plot to paint history as a binary story of suppressors and victims.

Such gross mischaracterizations have captured so much attention that they threaten to undermine any promising efforts by schools to teach important pieces of our history that have too long been overlooked.

Pieces like the Mendez case.

Mendez, et al vs. Westminster was one of the most consequential court cases in U.S. history, and it happened right here in Orange County. Without Mendez, there might never have been Brown vs. Board of Education, the landmark ruling that desegregated public schools nationwide and helped establish our state as a trendsetting powerhouse of public policy.

Newport-Mesa Unified officials responded quickly to the discovery of an age-inappropriate book found in an elementary school library. But the book itself tackles issues many teens face with little structural support.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of Mendez, which began with not one, but two injustices.

In the 1940s, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez moved their family to Westminster to farm land owned by a Japanese family that had been sent to a World War II-era internment camp. When the Mendez’s tried to enroll their children in the local elementary school they were turned away.

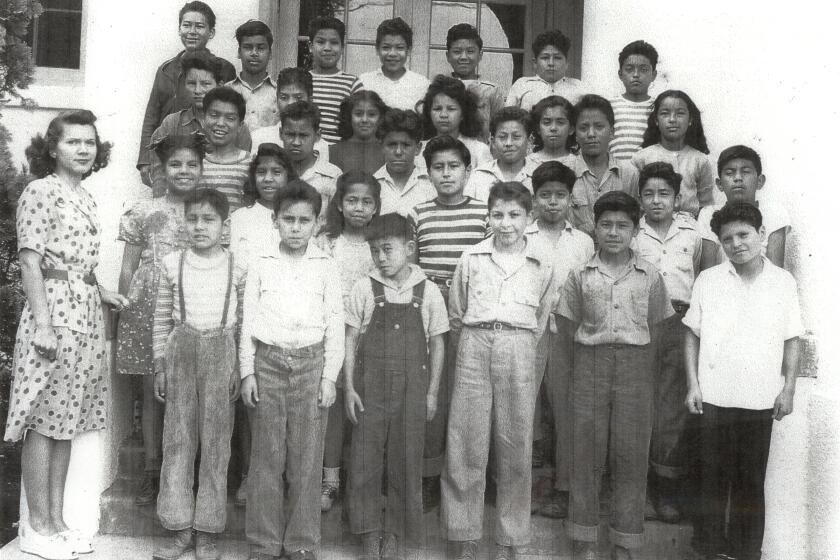

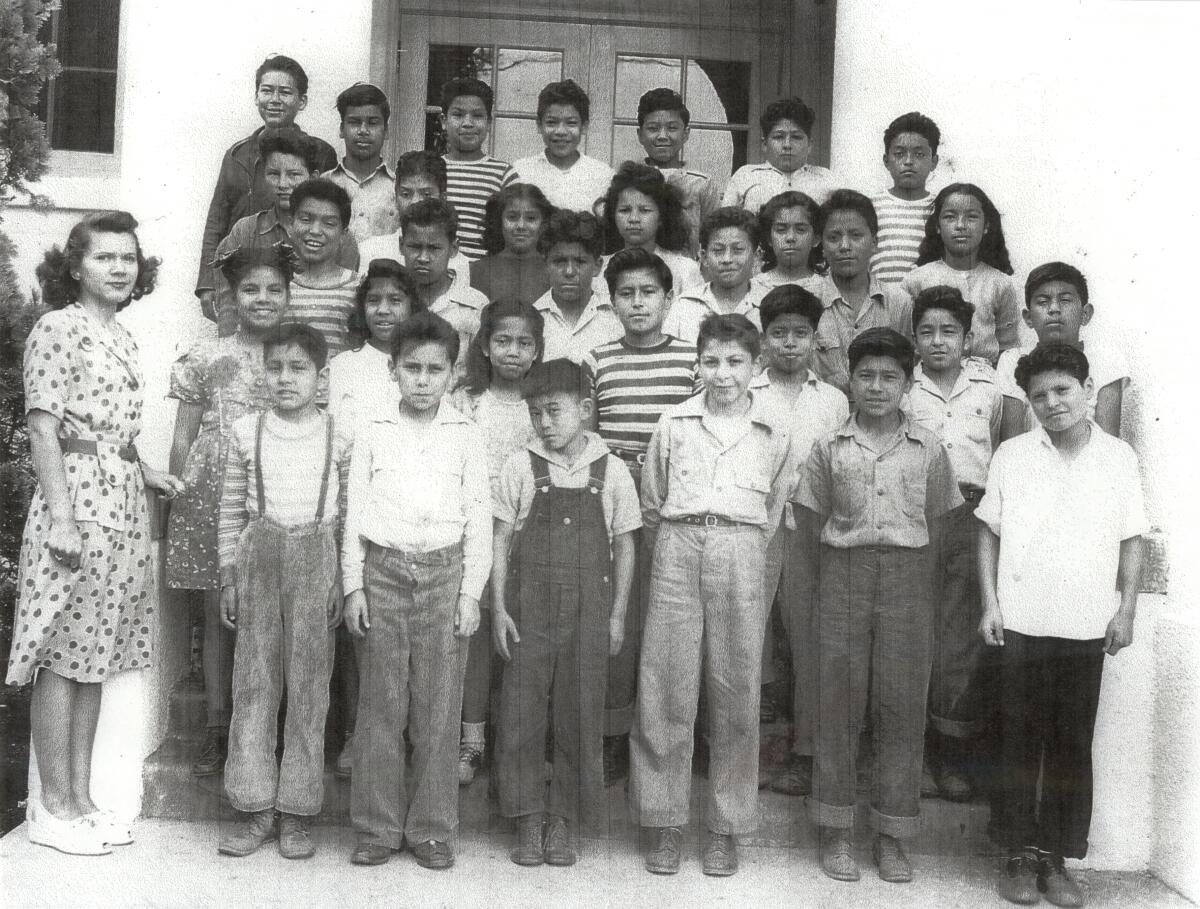

Figuring it must be a mistake — the Mendez’s were U.S. citizens and lived within the school’s boundaries — they appealed to the Westminster School District and the county but were again denied. They were told the children must attend the “Mexican” school, which was farther away and had inferior facilities.

They decided to fight. The Mendezes hired Los Angeles attorney David Marcus, and four other Orange County families — with the surnames Ramirez, Palomino, Guzman and Estrada — joined in the lawsuit against the Westminster, Garden Grove, Santa Ana and El Modena school districts. The plaintiffs argued that 5,000 children in the county were harmed by unjust discrimination policies.

In a then-novel strategy, Marcus used expert testimony to show that segregated schools resulted in feelings of inferiority among students of Mexican heritage, which jeopardized their ability to become productive citizens.

They ultimately triumphed in their quest to desegregate county schools, at one point joined by civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice but was then representing the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Two months after the final decision, California Gov. Earl Warren signed a bill outlawing school segregation statewide. And years later, Warren was the U.S. chief justice and Marshall was lead counsel when Brown, which borrowed heavily from the Mendez case, was decided.

Sandra Robbie, the woman who posed the question at the show I attended, is on a mission to spread the word about Mendez.

Robbie, a third-generation Mexican American, was born in Arizona and raised in Westminster. After graduating from UC Santa Barbara, she moved back to Orange County, worked, married and raised two children. In search of a fulfilling career, she returned to school to study TV production.

An appellate court upheld a ruling against Mexican schools 75 years ago. The pandemic roots of school segregation in Santa Ana remain forgotten.

One day she came across a news article about a school building named in honor of Mendez. It was her first introduction to the case.

“Reading about segregation that happened in my town, I could feel the kitchen walls spinning around me,” Robbie told me recently. “By the time I finished reading the article I felt like I’d taken a punch to my body. I felt angry, proud, all these emotions. When I was done reading I felt by the time I was done everyone was going to know about Mendez.”

In 2002, she produced a short documentary, “Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children,” and in the 20 years since she has furthered her quest through speeches and media coverage, and scored an invitation to a White House celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month.

“If I met you anytime in the past 20 years in two minutes I’d be telling you about Mendez,” she said.

In recent years, the case has finally begun to garner some of the attention that had long eluded it, thanks to the efforts of one of the Mendez children, Sylvia Mendez, who is now in her 80s, and others, including Robbie, who are determined to ensure that this momentous event isn’t lost to history. Mendez is now included in California’s model ethnic studies curriculum, but Robbie stressed that there’s still work to be done to inform teachers about the case and its impact.

Robbie has a line I’d like to borrow: “The stories we tell tell us who we are and who we can be.”

History is a complicated stew that invites deep and thoughtful analysis. Schoolchildren should be taught the whole of it, complexities and all, and learn that “who we can be” includes the stories they will help write.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.