Commentary: Rapid search for COVID-19 vaccine faces undue skepticism despite life-saving potential

- Share via

From 1999 to 2008, then-South African President Thabo Mbeki’s denial that that HIV caused AIDS led to hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths, Harvard researchers later concluded.

For decades tobacco companies battled against the overwhelming scientific consensus regarding the harmful effects of smoking. We all know how that turned out.

And in 1998, a paper in a medical journal that drew a link between certain vaccines and autism fueled skepticism about vaccine safety that persists and continues to proliferate, even though the paper was thoroughly discredited and later retracted.

Other myths about vaccines — including the common belief that they frequently cause the very illnesses they are designed to prevent — have contributed to lowering immunization rates and disease outbreaks in many communities.

These instances of science denial provide cautionary tales for these turbulent times, when mistrust of institutions and professional expertise has been revealed to run stubbornly deep within certain segments of American society.

Orange County reported three coronavirus-related deaths and 322 new infections on Saturday in data released by the Orange County Health Care Agency.

Now we find ourselves at a particularly fraught point, given the possibility that at least one COVID-19 vaccine will be made available in the coming months.

The introduction of a Covid vaccine for the coronavirus will undoubtedly further heighten the controversy over vaccine safety, especially given the mixed messaging about how fast researchers are working and worried speculation that shortcuts in the development process might be taken. Many people who are inclined to be skeptical about vaccines generally will be reluctant, to say the least, to try a new one.

But this time around those longstanding vaccine deniers will be joined by others who have previously had no qualms about receiving the recommended vaccinations, but who are now worried that a vaccine will be rushed into distribution before it’s proven to be safe and effective.

Some polls have found that a large percentage of Americans say they’ll refuse a COVID-19 vaccine, despite assurances by many researchers that they won’t compromise on following established scientific methods.

The situation is further complicated by the tragic failure of our nation to consistently adhere to the public health measures that are needed to get the spread of the virus under control while we wait for a vaccine. Those steps include social distancing, the faithful use of masks, widespread testing and contact tracing.

It must be a tough time to be a scientist.

“I’m very, very frustrated about the disdain in general for science,” said Dr. Don Forthal, a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at UC Irvine. “It’s hard to know to what degree this general mistrust of science will impact the use of a vaccine when it becomes available.”

If a well-tolerated and effective vaccine is ready for distribution and a large portion of the population refuses to take it, Forthal said, “we’ll still have a lot of people falling ill.”

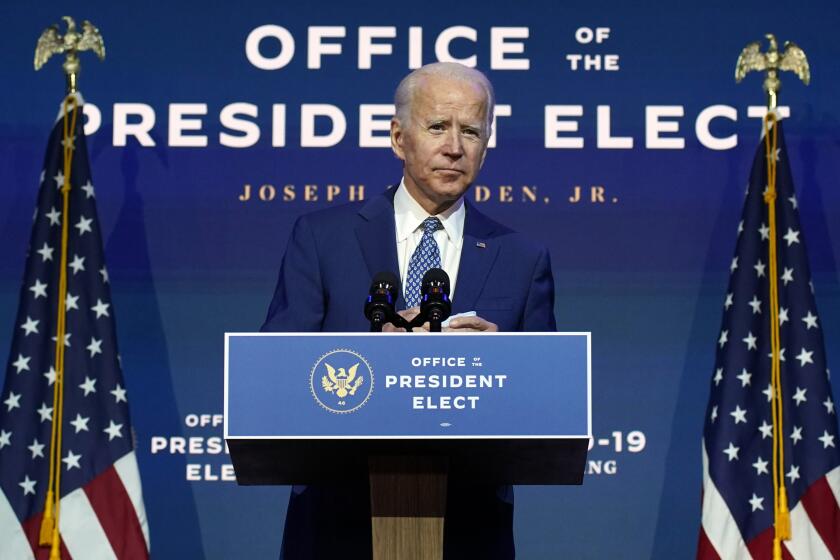

The swift unveiling of the coronavirus advisory board signals the urgency of the issue and its importance in propelling Biden to the White House.

Suspicions about a COVID-19 vaccine might also arise because of the reality that there is much that scientists have yet to learn about the virus and how to fight it.

It will take time — many years possibly — to fully understand how effective and long-lasting a vaccine will prove to be, and how successful scientists will be in keeping up with all the mutations that arise and which lead to different strains of the virus circulating in the population.

Yet as we’ve already seen, many people fail to understand that this is exactly how science works — that it is a painstaking, methodical process of experimentation and study that leads to discoveries and expanded knowledge. It’s not an all-or-nothing enterprise.

That’s why vaccines aren’t perfect, and we shouldn’t expect them to be. But they are demonstrably effective at tamping down, and in some cases even successfully wiping out, terrible diseases.

Dr. Michael Buchmeier is a professor of infectious diseases at UC Irvine’s medical school and associate director of the Center for Viral Research. He has worked on vaccines for 42 years, and he had hoped to retire earlier this year. Then the pandemic hit and he decided to put those plans on hold.

It was impossible to miss the exasperation in his voice when I spoke with him by phone. The spread of this coronavirus is difficult to contain because of its highly contagious nature, he said, but “it’s also harder to stop when the country is as divided as we are, and getting people to follow simple guidelines” is controversial.

“This is the one thing that should have united us,” he said. Instead, “people are not showing common sense.”

Those of us who are not scientists but who firmly believe in the scientific process can only hope that those among us who cling to denial, or who willfully misunderstand the nature of science and public health, will at last wake up and embrace the needed common-sense measures.

And whenever a vaccine for COVID-19 does emerge, I also hope that enough people will give credence to whatever the scientific consensus tells us about its safety and efficacy, instead of following bizarre conspiracy theories and internet rumors.

If we’re ever going to get out of this mess, we’re going to have to start respecting expertise again.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.