Review: John Hurt is magnificent in Beckett’s ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’

- Share via

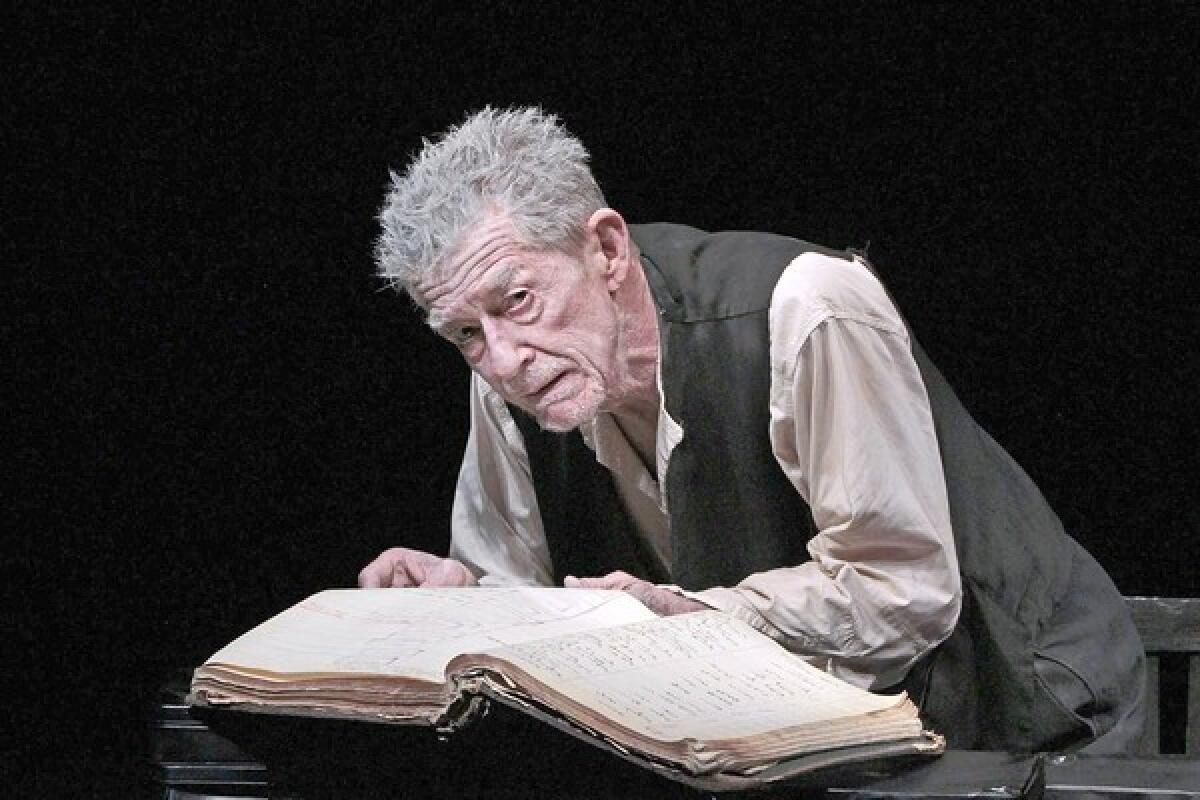

With his shock of silver-gray hair, his face etched by time with the lean expressiveness of a Giacometti sculpture and his soulful eyes registering every fleeting hurt and happiness, John Hurt bears a striking resemblance to Samuel Beckett in the distinguished British actor’s magnificent rendition of “Krapp’s Last Tape” at the Kirk Douglas Theatre.

For anyone needing a reminder that theater can be an art (and not just a scrappy entertainment), this beautifully mounted production of Beckett’s play, directed by Michael Colgan of Dublin’s Gate Theatre, is not to be missed.

Lighted by James McConnell with a neo-Rembrandtesque intuition of the interplay of light and dark, the piece should be approached as a living canvas, an installation more than a traditional drama. Verbally precise but equally deft with silence and movement, this incarnation of “Krapp’s Last Tape” bears witness to the silent consciousness of living.

Beckett wrote this roughly 55-minute theatrical poem for the Irish actor Patrick Magee, whose voice had a cracked, world-weary lilt to it. But it’s one of his most personal works, a piece that even the famously unconsoling Beckett himself called “nicely sad and sentimental.” Ever ready to enjoy a joke, Beckett confided to a friend, “People will say: good gracious, there is blood circulating in the man’s veins after all, one would never have believed it; he must be getting old.”

The play, first produced in 1958, isn’t about Beckett, but it’s infused with his history, emotion and abiding sense of irony. Hurt may look like the playwright here, but of course he’s portraying the teasingly named Krapp. (As always in Beckett, bathroom humor, with its casual acceptance of the disintegrating body, is raised to an existential category.) Yet in a virtuoso solo acting turn that is as technically accomplished as it is acutely felt, Hurt channels Beckett’s compassionately rueful comic spirit, delighting in the free intermingling of somber philosophical themes and subtle slapstick.

The dramatic situation involves an elderly man, a writer, sitting at his desk and preparing to listen to audiotape diaries he made 30 years earlier. Before he does, however, he gobbles a couple of bananas stored in his desk and retreats to an off-stage backroom for some routine alcoholic refueling.

“Thirty-nine today, sound as a bell, apart from my old weakness, and intellectually I have now every reason to suspect at the … [hesitates] … crest of the wave — or thereabouts,” the voice of his early-middle-aged self announces.

He has carefully dug up this entry from box three, spool five — the word “spool” providing this wordsmith with an innocent pleasure that Hurt embraces like a child handed a toy pipe.

Life has dwindled for Krapp into aches, stomach ailments and regrets. The biggest regret involves his parting with a woman who offered a “chance of happiness,” one his ambition as a writer and personal limitations didn’t allow him to seize.

The voice on tape recalls the couple’s fateful ending: “I said again I thought it was hopeless and no good going on, and she agreed, without opening her eyes.”

With ruthless economy, Beckett captures the weight of what wasn’t to be. And Hurt, employing a gestural vocabulary that is just as spare, communicates the terrible waste of this opportunity with just a few half-conscious caresses of the tape machine as it recounts the doomed romantic affair.

“Krapp’s Last Tape” isn’t all about love and loss. There’s much wry amusement in the contradictions of the character at different stages of his life. Like Proust, Beckett understands that we don’t die a single time but are continually sloughing off earlier selves in a mortal succession that relentlessly drives home our ultimate end.

Krapp can’t for the life of him recall the “memorable equinox” he once assumed he’d never forget. The word “viduity” (“state or condition of being or remaining a widow or widower”), at one point a readily retrievable word in his lexicon, now requires a trip to the dictionary. And all those resolutions to cut down on liquor and those difficult-to-digest bananas strike him as laughable from his current high perch of years.

A master of reticence, Hurt (unforgettable in “The Elephant Man”) has had a prolific and highly various film career (“Midnight Express,” “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy”). Beyond his seamless craft, there’s a reason he’s still so in demand. His face is the single most powerful argument against plastic surgery I’ve come across on stage. Every wrinkle, every bag, every reddened crease testifies to our common condition.

Hurt eloquently deploys this beautiful monument of aging in the service of Beckett’s vision. He has been performing the role for quite some time, but there’s nothing stale in his characterization. This is an actor in vintage form in a play that is as soft as it is stark.

Krapp’s recognition that the dark he has “always struggled to keep under is in reality” his most “unshatterable association” becomes in this production more than just one man’s truth.