UCI researchers’ invention could lead to longer-lasting batteries

- Share via

In an age when battery life is precious and charging multiple times a day may actually deplete a battery’s life span, UC Irvine researchers have assembled materials that could help solve that problem for the world’s device users.

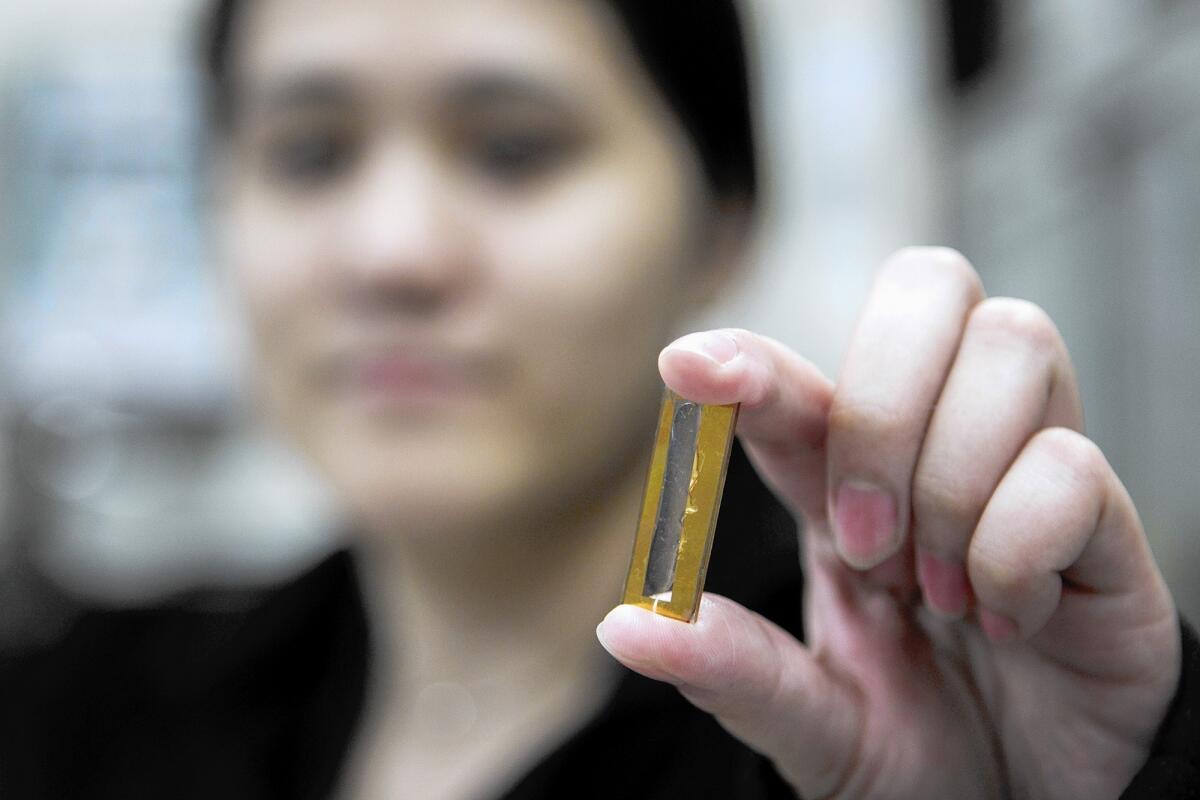

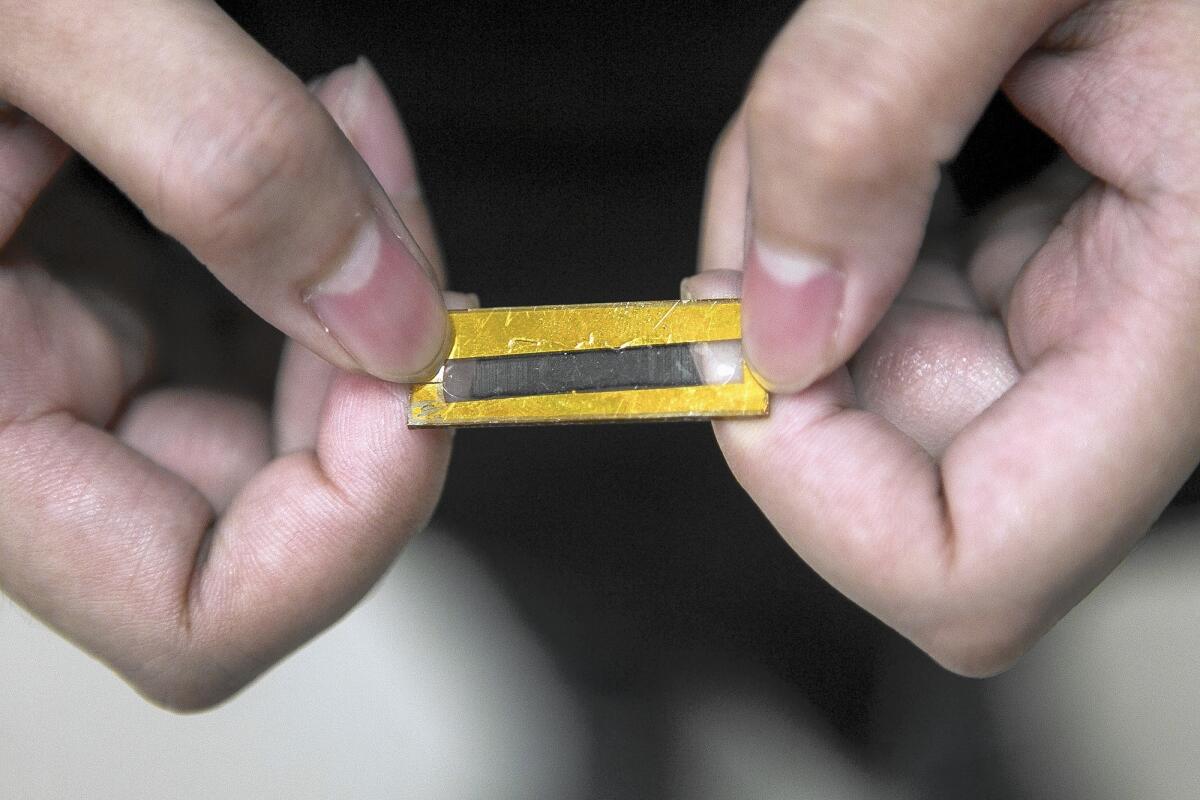

Their creation — 2 inches long and about a quarter-millimeter thick — can be recharged hundreds of thousands of times without losing capacity.

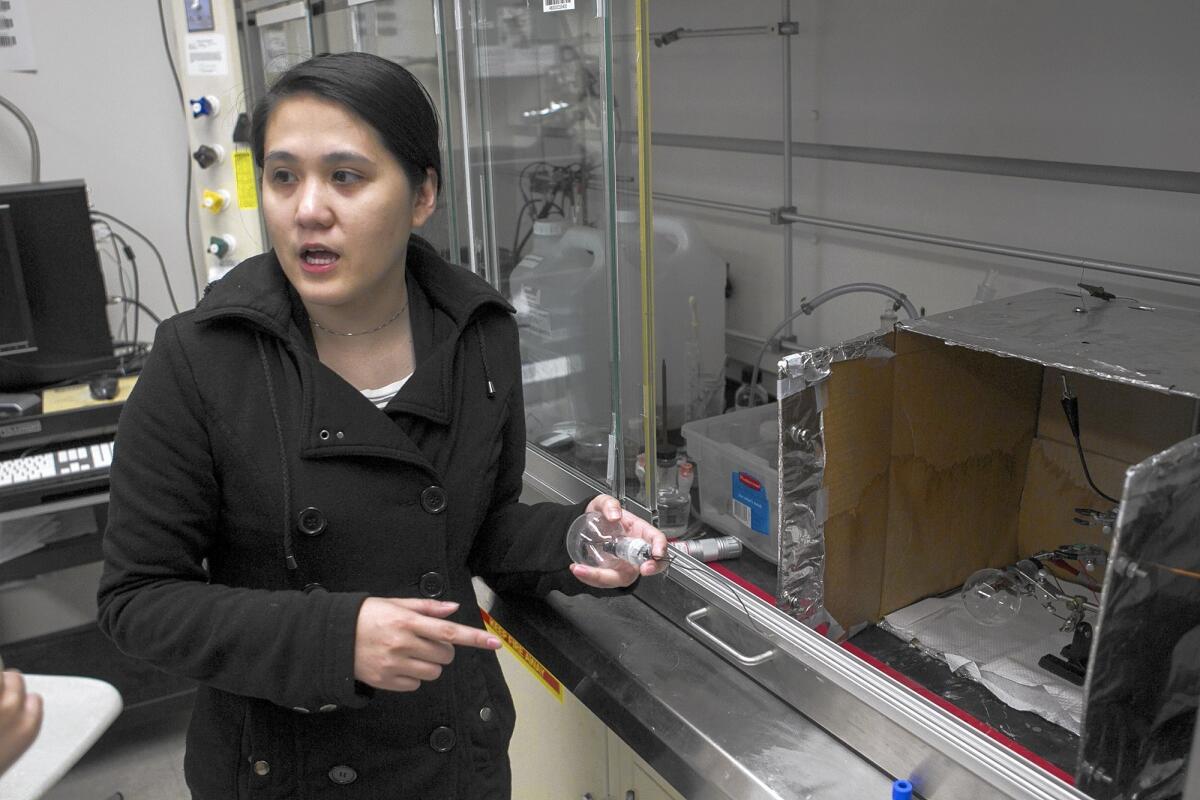

The study’s leader, UCI chemistry doctoral candidate Mya Le Thai, began work on the device, known as a capacitor, in 2015. She developed the project with the help of several other graduate students and the guidance of Reginald Penner, chairman of UCI’s chemistry department.

A capacitor is used to store an electric charge.

“The goal is to make it so that it doesn’t degrade so we can save materials and save resources,” said Thai, 28. “Today, people charge many devices for work or at home, so either we come up with a new battery or a new way to recycle them.”

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

She hopes the device can lead to the creation of longer-lasting batteries for phones and maybe satellites.

The capacitor has three key components: a gold nanowire, an inorganic compound known as manganese dioxide and a Plexiglas-like gel.

Nanowires, which are thinner than a strand of hair, are highly conductive but fragile.

According to Thai, a nanowire in a typical battery is prone to flaking when the battery is being charged or discharged.

“A lot of current is going through it and then it loses material,” causing capacity to degrade, Thai said.

But with the capacitor’s gold wire coated with manganese dioxide and layered with the gel, the materials are protected, Thai discovered.

“Usually, it doesn’t work quite this way right away, so we were really surprised,” Penner said. “The idea of using gel with nanowires is a new idea.”

Thai charged and discharged the capacitor through 200,000 test cycles in a lab over three months. Afterward, she found no cracks in the nanowire, and the capacity had not degraded at all, she found.

“About 10,000 or maybe even 20,000 would be a pretty good lifetime” for a typical battery, Penner said.

Thai plans to research why the gel works with the device and if there are gels made of other components that would help the capacitor perform better.

The capacitor study was done with funding from the Basic Energy Sciences division of the U.S. Department of Energy and in coordination with the Nanostructures for Electrical Energy Storage research center at the University of Maryland.

Twitter: @AlexandraChan10