New 4-year cloud-seeding pilot program hopes to make it rain in Santa Ana River watershed

Using meteorology and chemistry to help prod Mother Nature, water officials have begun seeding storm clouds throughout the Santa Ana Watershed to boost regional water supplies by enhancing the rain and snowfall produced during storms.

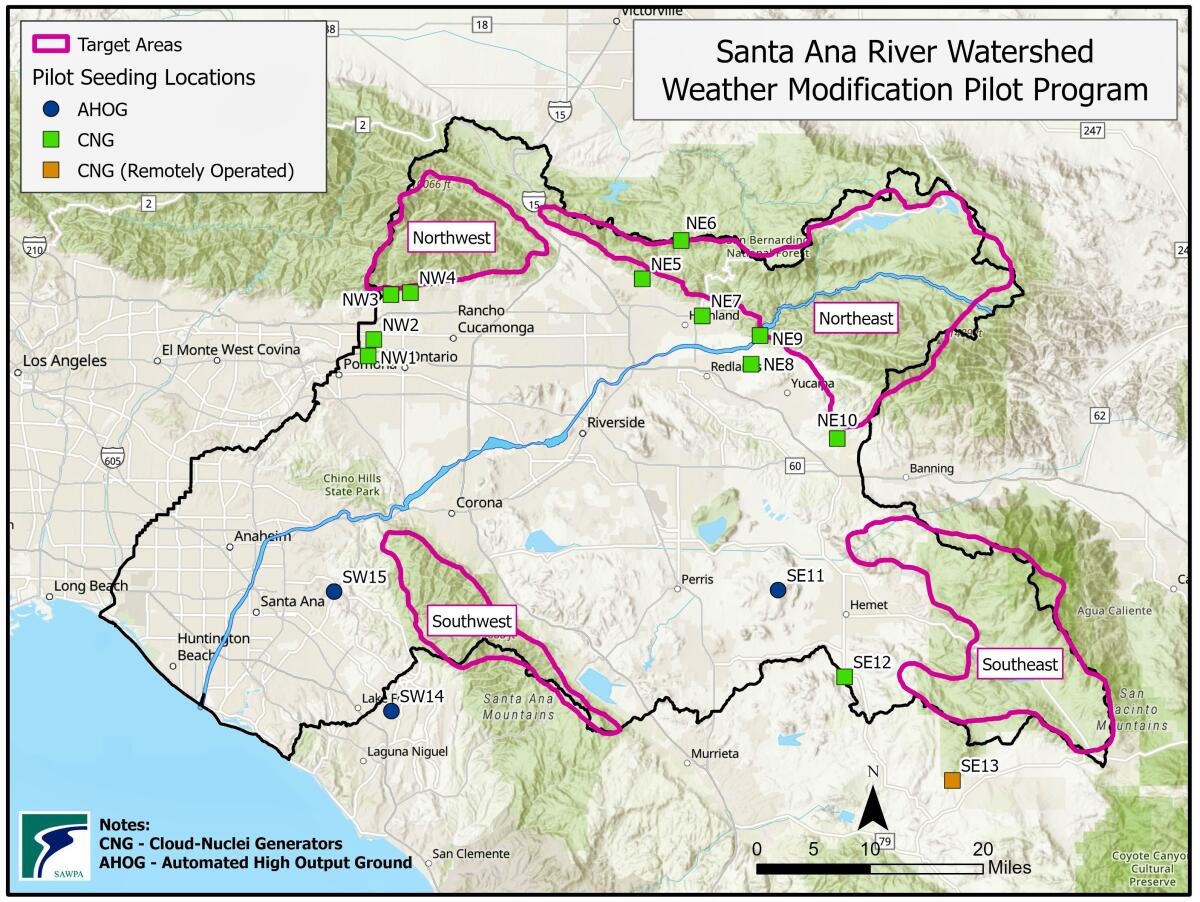

Started in November as a four-year pilot under the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority — a joint powers authority comprising five public agencies, including Orange County Water District and others in the Inland Empire, San Bernardino and Riverside — the project aims to increase precipitation levels anywhere from 5% to 15%.

Officials estimated in a 2020 feasibility study that, on the southwest end of the watershed in Orange County, cloud seeding could add .59 inches of seasonal rainfall, amounting to nearly 450 additional acre-feet of natural streamflow, or a 9.7% increase.

Cloud seeding involves releasing particles of silver iodide into the air during a storm event — in this case, not from airplanes but from about 15 ground-based seeding systems installed on high ridges to the north and south of the watershed’s natural basin.

Issued from flares, in which acetone combusts to help the particles take flight, the floating silver iodide acts as a nucleus or form, to which supercooled water molecules in the air can attach. Its snowflake-like structure encourages molecules to condense into water droplets or ice inside a cloud system.

Two such installations in remote but protected locations in Lake Forest and the city of Orange make up the southwest component of the project, operated by Utah-based contractor North American Weather Consultants. Particles from these stations will ride air patterns that jet from the Pacific toward the northeast rim of the watershed.

SAWPA General Manager Jeff Mosher said the basic idea is to augment the naturally occurring precipitation flowing into the 2,650-square-mile watershed’s dams and basins, replenishing the overall supply, which serves 6 million residents across four counties.

“This doesn’t create clouds,” he said Wednesday. “What it does is help ice and snow formation in the existing storm clouds. It enhances that process, so more precipitation falls.”

The Nevada-based Desert Research Institute will compile rainfall data and mathematically determine the increase in precipitation in four target areas around the watershed during each rainy season of the project’s four-year span to see where the water ended up. Seeding would be paused, via remote control, during high rain events to prevent flooding.

Although the idea of releasing chemicals into the atmosphere sounds environmentally questionable, data compiled from areas where cloud seeding has long been employed indicate the process produces minute amounts of silver iodide and carbon dioxide, the latter being a byproduct of vaporized acetone.

“Because silver iodide is so inert, it doesn’t have much of an impact on the ecology or on public health,” he said. “In Santa Barbara, where it’s gone on for 30 or 40 years, there’s been no increase in silver iodide backup in the soil where they cloud seed.”

The cost of SAWPA’s four-year pilot is roughly $1.2 million, roughly half of which was funded by a grant from the California Department of Water Resources, according to Mosher. The remainder was split evenly between the agency’s five member districts.

Once the program is complete and the numbers have been crunched, districts may choose to extend or expand their participation and financial involvement or opt out altogether.

Bruce Whitaker, who serves on the Orange County Water District Board of Directors and chairs SAWPA’s Board of Commissioners, said the prospect of enhancing local water recovery is appealing.

“In most years our potential for rain is limited to several weeks, at most, so our ability to maximize the potential capture during that short rainy season is very significant,” he said Thursday.

If cloud seeding brings more water in the county’s groundwater basin, agencies who use those resources may eventually be able to rely less on imported water from regional Metropolitan Water District stores — obtained from Northern California’s diminishing sources — at a fraction of the cost.

“The potential cost savings are really very large,” Whitaker said. “Northern California doesn’t like to ship their water to us in Southern California. In years of drought they keep reducing the amount they give us. To be resilient, we have to create more water sources.”

Mosher said making more rain and snow would not only increase regional water reliability today but help build better climate resilience in the years ahead.

“The main objective is reduced reliance on imported water and becoming more reliant on locally produced water,” he added. “If it provides us with a 5%, 10% or 15% [increase] that’s more water to store in aquifers — it’s a hedge against climate change.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.