Mater Dei football players allegedly sexually assaulted teammate, police record says

A handful of short sentences written by a police dispatcher laid out the allegation in stark detail.

In a locker room at Mater Dei High School in Santa Ana, several football players forced a teammate to the floor and exposed their genitals. Then they held him down, as one player “began humping” him from behind, through his pants.

The incident happened in late August, according to a Santa Ana Police Department document, two weeks after the student started school at Mater Dei, home to one of the country’s most celebrated high school football programs. He wasn’t physically hurt, but the episode left him suffering from anxiety, police said in the document. He left Mater Dei shortly afterward.

The document, which The Times obtained through a public records request, is a single-page, eight-sentence description of the alleged assault that the Police Department entered into its computer system Sept. 16. The document does not address whether the Aug. 31 claim of sexual assault was investigated, or whether students, school officials or family members contacted police.

The document said the incident was reported to the student’s coach, who informed “school officials,” but did not specify when. The police received secondhand information about the incident from social services, the document said.

A lawsuit accuses Mater Dei and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange of trying to cover up a brutal locker room altercation that left a player with a traumatic brain injury.

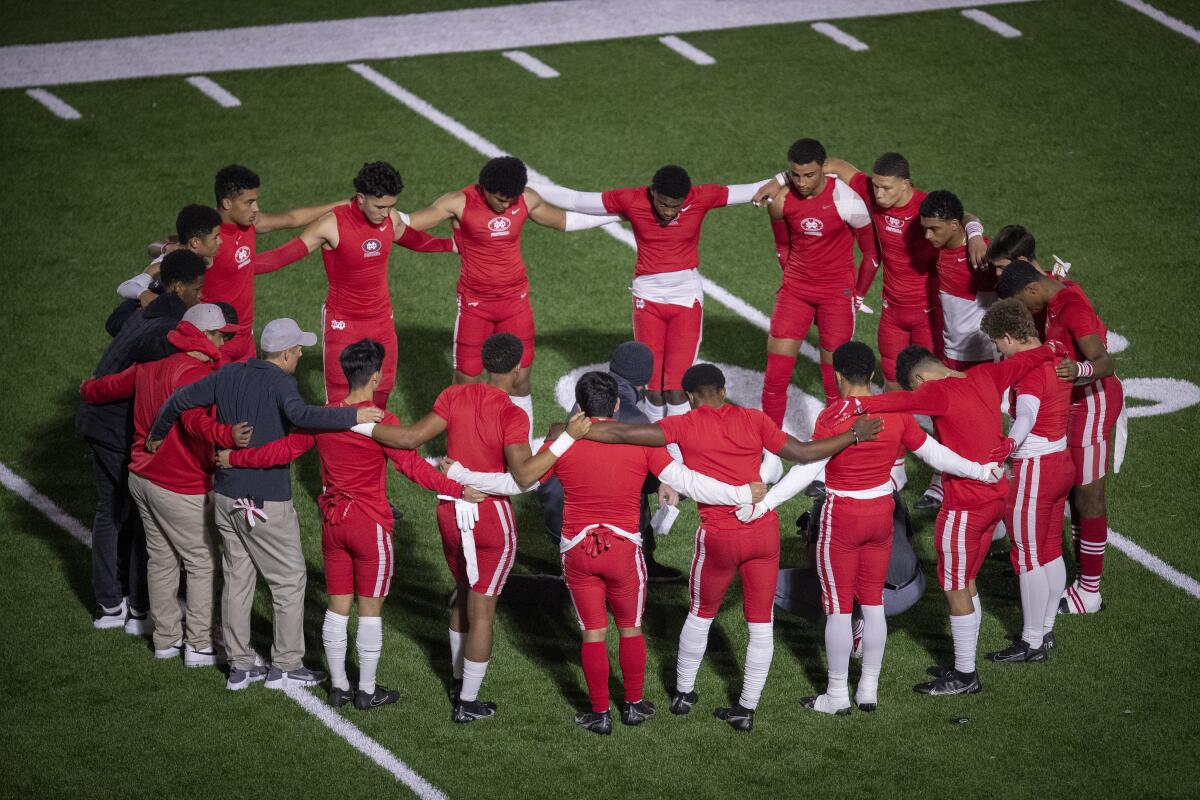

The allegation of sexual assault, which has not been previously reported, raises questions about Mater Dei’s stated commitment to student safety and transparency in its storied athletics program. It also highlights concerns about the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange’s standards of behavior and sportsmanship for its athletes, many of whom are closely watched by college scouts.

“It is, and has long been, the Diocese of Orange policy not to comment on matters involving minors, including incidents regarding current and former students,” Bradley Zint, a diocese spokesperson, said Monday.

The Times does not typically identify people who have reported being victims of sexual assault. A representative for the student’s family declined to comment.

What goes on in Mater Dei’s locker rooms has become a flashpoint in Orange County since the family of a former football player sued the school and the diocese in November, alleging a culture of hazing and secrecy and a win-at-any-cost attitude.

The family alleged in their lawsuit that their son, who was new to the football team, was forced to fight a much larger player in a locker-room hazing ritual in February 2021. The school tried to cover up the student’s injuries, which included a concussion and a broken nose, by not calling paramedics and not contacting his family for 90 minutes, the lawsuit said.

“Everything from ... when he walked out of the locker room to the silence after was handled wrong, in my opinion,” Amanda Waters, the former athletic director of Mater Dei, said in a sworn deposition filed in Orange County Superior Court in April.

Exclusive: The parents of a former Mater Dei football player injured during initiation explain why they filed a hazing lawsuit against the school.

At the end of the fall semester, Mater Dei hired a Sacramento law firm, Van Dermyden Makus, to conduct an investigation of safety practices in the school’s athletic programs. The review was ordered by Father Walter E. Jenkins, then the president of the school, who left Mater Dei over winter break after six months on the job.

The school has said the change in leadership will not affect the investigation. New school President Michael Brennan told The Times in February: “We’re not going to hide anything. We’re going to be completely transparent.”

The assessment is “ongoing,” Zint said. It is not clear when it will be completed.

The family of the boy injured in the locker room in February 2021 said his injuries stemmed from a ritual called “Bodies,” in which two players punch each other between the shoulders and the waist until one gives up. The larger of the two teens punched the other boy three times in the head, two videos reviewed by The Times showed.

The diocese’s lawyer, Maria Roberts, said in a court filing this month that because the student was already a member of the football team when the incident occurred, it did not qualify as hazing.

A longtime educator with experience overseeing high school athletic programs will take the helm of Mater Dei amid a controversy over an alleged hazing scandal.

“By definition, hazing only applies to a method of initiation or pre-initiation when a student is seeking membership in an organization,” she wrote.

His parents told The Times that players who did not participate in the initiation rite were ostracized and sometimes had their lockers soaked in urine.

Bruce Rollinson, head coach of Mater Dei’s football team, told the boy’s father that he “would be a millionaire if he got paid $100 every time he heard about Bodies or other physical rituals” among the students, the lawsuit said. Rollinson later told the police he had no knowledge of the game, the lawsuit said.

Waters, the former athletic director, said in a sworn deposition that the morning after the altercation, Rollinson told her: “If I had a dollar for every time these kids played bodies, I’d be a millionaire.”

Minutes later, Mater Dei Vice Principal Geri Campeau — who has since left the school — went to Waters’ office, shut her door and began yelling “about how I need to stop asking questions,” Waters said in the deposition. She said she was told not to question Rollinson about the incident again. That struck her as odd, she said, because it suggested that she “couldn’t care if a kid was OK.”

Waters left Mater Dei six weeks later. The aftermath of the locker-room fight was a factor in her departure, she said, because “how it was handled was completely against everything that we had spoke about prior to me being hired.”

Waters said in the deposition that she had talked to Rollinson at least 10 times about monitoring the football team’s locker room to ensure that students complied with COVID-19 protocols. Rollinson was one coach “that wouldn’t do it,” she said.

His response, she said, was always the same: “I don’t have time to do that s—.”

Waters said she was concerned that football players were in the locker room unsupervised between the time they lifted weights and when they started football practice.

She said in the sworn deposition that she was surprised adults had not intervened in the Feb. 4 altercation because the school had taken steps to ensure the locker room wasn’t left unsupervised. Mater Dei had hired security guards for the football locker room, she said, and an associate athletic director often stood outside the door.

Early in her nine-month tenure at Mater Dei, the football locker room saw some “destruction,” including a sink ripped out of the wall, and a broken toilet and mirror, Waters said.

“Teenagers unsupervised is a recipe for disaster,” she said.

A string of troubling revelations about the conduct of Mater Dei athletes emerged after the Bodies suit was filed, including a lawsuit first reported by the Orange County Register alleging that two football players broke a basketball player’s jaw at the behest of another student.

Older videos of Mater Dei football players in the locker room also began to circulate.

The details of the beating, described in a May lawsuit, follow weeks of controversy for the storied Santa Ana football program.

One 40-second video, originally posted to Snapchat, showed a throng of players standing in a circle in the locker room. They whooped and laughed as a shirtless player pulled down his shorts to moon them, then simulated a lap dance and an oral sex act on a clothed player sitting in a chair. The caption on the video read: “Miss Summer Ball.”

Another video contained a compilation of more than a dozen cellphone videos, set to a remix of Nicki Minaj’s “Boss Ass Bitch.” The videos included footage of a player throwing a T-shirt over his teammate’s head and tackling him, and two clips of players sitting on the toilet, including one taken with a phone that had been shoved under a bathroom stall door.

Jenkins told the Register just before his departure that both videos would be included in the law firm’s investigation of the athletics program.

Daniel Cha, a lawyer for the family whose son was injured in the locker-room altercation, wrote in a court filing this month that Mater Dei “seems to forget they operate a private school filled with children entrusted to their care, which comes with it significant obligations to protect those students.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.