Before O.C. oil spill, platform owner faced bankruptcy, history of regulatory problems

The owner of an offshore oil operation that spewed at least 126,000 gallons of crude oil into the Pacific Ocean and fouled Orange County beaches had emerged from bankruptcy just four years ago and amassed a long record of federal noncompliance incidents and violations.

As divers for Houston-based Amplify Energy Corp. on Sunday searched for the location and cause of the massive leak, public records revealed a pattern of changing ownership and compliance warnings for the company. Amplify had also been working to upgrade its aging infrastructure and had plans to initiate new drilling near the site of the leak in the final three months of this year, according to company records. It remains unclear whether the drilling had commenced or whether the work was connected to the leak.

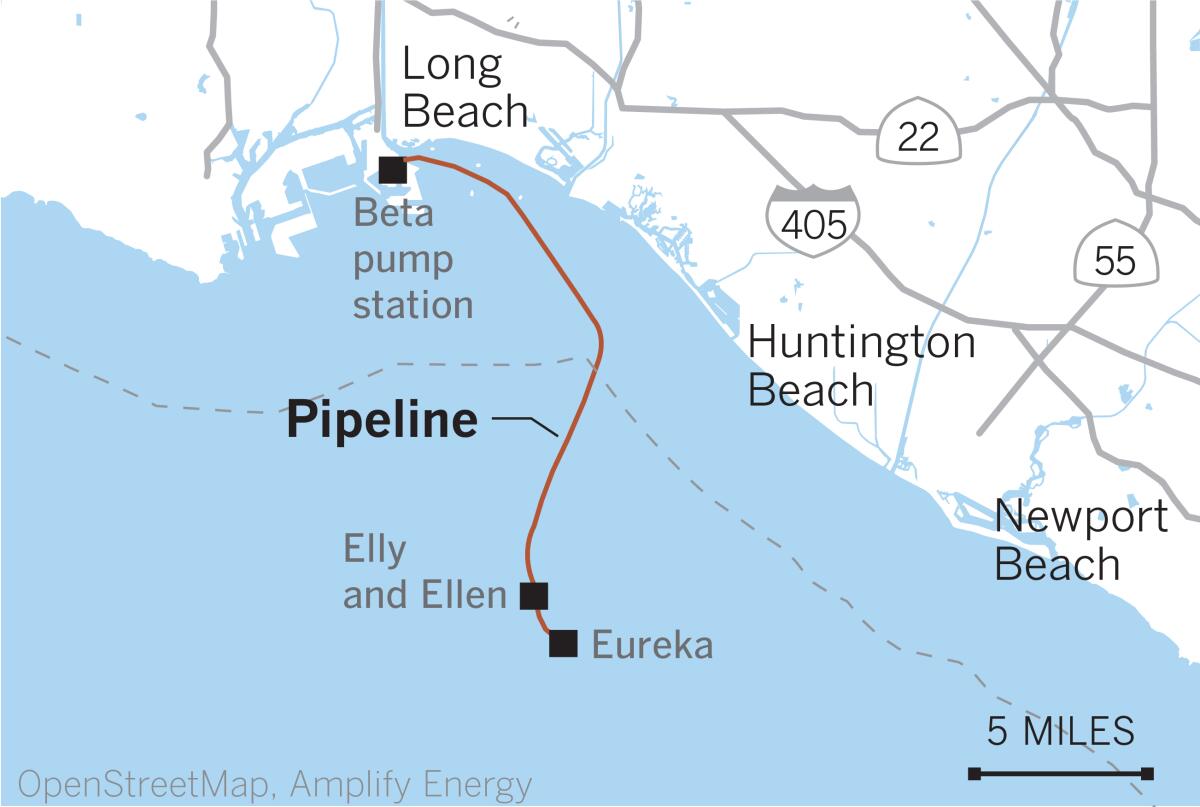

Government officials say the spill originated from a broken pipeline off the coast of Huntington Beach that runs from the Port of Long Beach to a production and processing platform called Elly, located in the Beta Field, an accumulation of oil nine miles from the California coast. Drilling in the Beta Field, discovered by a consortium led by Shell Oil Co. in 1976, began in 1980 and oil production started in January 1981.

The exact cause of the leak remains unclear. But the devastating scope of the spill is already renewing calls for the government to take more aggressive action against the aging oil platforms that dot the Southern California coast. Environmental groups have raised the alarm for years about the condition of some of the systems and what they consider a lack of oversight.

In 2018, Miyoko Sakashita, oceans program director for the Center for Biological Diversity, and other environmental advocates took part in a fact-finding cruise along the California coast to inspect about a dozen oil platforms, some more than 40 years old. They saw rusted pipes and equipment and used an optical gas imaging camera to document flaring incidents on several platforms, she said.

“So much of that infrastructure is old and corroded,” Sakashita said. “[The platforms] should have been decommissioned. ... It’s not a robust system of oversight.”

Orange County Supervisor Katrina Foley said a broken pipeline connected to an offshore oil platform called Elly caused the spill.

Although California banned new offshore oil operations decades ago, platforms such as Elly continue to operate in federal waters — more than three miles from the coast.

Beta Operating Co., a subsidiary of Amplify Energy, operates Elly. The offshore facilities platform processes and routes crude oil from Ellen and Eureka, the firm’s two oil production platforms in the Beta Field, to an onshore pumping station in Long Beach via the 41-year-old, 17.3-mile San Pedro Bay Pipeline.

On Sunday, Martyn Willsher, Amplify’s president and chief executive, said the company notified the Coast Guard on Saturday morning after workers conducting a line inspection noticed a sheen in the water. He said that they don’t know when the leak started but that it appears to have occurred 4½ miles from shore. He added that the company has not had previous issues with the Beta Field infrastructure.

“We’re still investigating whether it’s a leak, a more substantial leak,” Willsher said. “We don’t know yet until the divers have a chance to go down there and really investigate.”

Donald Boesch, who served on a federal commission formed to make recommendations after the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, said the infrastructure used by California’s offshore drillers is decades old, making it prone to failure.

There could have been a valve malfunction, or seabed erosion that exposed a pipeline to damage, Boesch said. “I can’t say that’s the case here, but one worries about older infrastructure.”

Boesch said he’s noticed that smaller businesses are buying up drilling operations from larger, more established players in the industry, and that these smaller companies seem to have more incidents such as leaks and pipeline ruptures. “They don’t necessarily have the resources to stay on top of safety and respond quickly,” he said.

That’s part of a broader push to phase out the oil and gas industry altogether, Boesch said — one that is important to addressing climate change but might pose other risks. The spill raises questions about “whether the industry is providing proper diligence to the declining production of resources,” he said.

Amplify has been upgrading its assets in the Beta Field throughout 2021. It completed “rig and facility upgrades” in the first half of the year, and Willsher announced in the company’s second-quarter earnings call in August that “a case hole recompletion” — a means of readying a well for oil production — was “progressing according to schedule” with initial results expected by the end of September.

Willsher also said during the August call that the company planned to undertake “two sidetracks of existing wells in the fourth quarter of 2021,” and that it expected the projects to begin producing oil by the end of the year. Sidetracking is loosely defined as drilling laterally from an existing well, often with a goal of reaching untapped oil stores.

The time it took to determine the scope of the leak has sparked questions from residents and others about how the early hours of the crisis were handled.

It’s unclear yet whether work on those upgrades was underway when the leak occurred, or whether it contributed to the release of oil into the ocean. But this was not the first incident at the Beta Field.

Between 2013 and 2014, federal regulators fined Beta Operating a total of $85,000 for violations that, in two instances, led to injuries of workers.

In one incident, a worker was not wearing the appropriate protective equipment and “received an electric shock of an estimated 98,000 volts at very low amperage,” according to federal records. In another violation, crude oil was released through “the flare boom” after a “safety device was bypassed … and was not properly flagged or monitored,” the records show.

Beta Operating has also been issued 125 noncompliance violations by federal inspectors, according to a database maintained by the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which is responsible for inspecting offshore oil platforms.

The violations include 72 so-called component and facility shut-in noncompliance incidents, in which violations had to be corrected before the company could continue the activities in question, as well as 53 additional noncompliance warnings for violations deemed not severe or threatening, according to the bureau. The database provides only the total number of violations and does not contain details about individual incidents.

In enforcing violations that are deemed not threatening or severe on oil platforms, federal inspectors with the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement allow the operator a “reasonable amount of time” to fix the violation, according to the bureau.

But environmentalists say the spill raises serious questions about whether federal regulatory agencies are adequately inspecting the aging equipment.

In June 1999, a corroded pipeline that carried oil, water and gas from the Eureka platform to Elly leaked 2,000 gallons of oil, which led to the Eureka platform being taken offline until 2008. At the time of the leak, the Beta Unit was owned by Aera Energy, a Bakersfield-based oil and natural gas company co-owned by Exxon Mobil Corp. and Shell Oil Co. The leak, which was the first of two along the 1.8-mile pipeline in 1999 and caused tar balls to wash ashore at one California beach, resulted in Aera being fined $48,000 for failing to properly calibrate a leak-detection system.

On Sunday, Willsher said that “everything is shut down” and that the pipeline was suctioned at both ends to stop the flow.

In early 2017, the Beta Field operation’s then-owner, Memorial Production Partners, filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 11, then emerged several months later as Amplify Energy. In March 2020, the firm announced that it had “lowered its 2020 capital expenditure budget by approximately $17 million or 37% in response to the recent severe decline in commodity prices and overall downturn in the market attributed to COVID-19 and OPEC’s decision to increase production.”

Willsher said Sunday that the Beta Field infrastructure had been “well maintained” throughout the pandemic.

“We’ve been committed to actually putting capital into this asset,” he said.

During Amplify’s earnings call in August, Willsher said the company puts a premium on returning value to its shareholders.

“This is kind of in our DNA to return capital to shareholders,” he said. “That’s kind of the whole methodology of the company is to be sustainable, free cash flow that could ultimately be returned to shareholders.”

Amplify has oil and natural gas operations in Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming, in addition to its Beta Field assets. As of 2017, the operation, known as the Beta Unit, had produced more than 49 million barrels of oil, according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. Before the first platforms went online 40 years ago, Shell and its partners estimated that the Beta Field contained about 150 million barrels of oil.

In California, distaste for offshore drilling dates to 1969, when a devastating 100,000-barrel spill occurred off the coast of Santa Barbara. Thousands of birds, drenched in oil, struggled to take flight. Sea otters flailed in the water, and day after day, the tide brought in dolphin carcasses. That spill galvanized the modern environmental movement and turned California into a leader in restricting offshore oil drilling.

The state, which has jurisdiction over tidelands and waters extending roughly three miles offshore, has not issued a new offshore oil and gas lease since 1969. In 1994, the state Legislature passed the California Coastal Sanctuary Act, which prohibits new leasing in state waters.

As for oil operations in federal waters — such as the one in the Beta Field — governors across party lines, as well as the State Lands Commission and California Coastal Commission, have fought off numerous attempts to expand offshore drilling, challenging federal efforts in court when necessary.

When the Reagan administration sought to open much of the nation’s outer continental shelves, for example, 24 cities and counties across California passed local laws banning new infrastructure that would support offshore drilling. Seventeen were sued by oil companies, but the local ordinances all still exist in some form today.

More recently, the Trump administration seemed intent on weakening the enforcement capabilities of the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which was created after the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster to make sure pipelines and drilling operations are abiding by proper safety measures. The administration in 2017 had tapped Scott Angelle, a veteran of Louisiana politics, to run the agency. Angelle was criticized as being cozy with the oil and gas industry.

Times staff writers Dakota Smith and Jaclyn Cosgrove contributed to this report.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.