Orange County’s bishop, a $12-million problem and a secret fight stretching to the Vatican

The FedEx envelopes landed at dawn on the doorsteps of some of Orange County’s most influential Catholic philanthropists — real estate developers, attorneys, CEOs and other church stalwarts who had raised tens of millions of dollars over the years for the local diocese.

Inside were letters from Bishop Kevin Vann that boiled down to two words: You’re fired.

Those June missives ignited a revolt inside the Orange County church that has burned all the way to the Vatican while remaining largely hidden from the diocese’s 1.3 million rank-and-file Catholics.

At its heart is a falling-out between a circle of well-connected laypeople who helped the church rebound financially from the clergy abuse scandal two decades ago, and a prelate staring down fresh money problems brought on by the pandemic and a new round of molestation lawsuits.

The benefactors have accused Vann of violating state law by removing them from the board of an independent charity after they rebuffed what they contend was an illegal plan to “invade” endowment funds and flout donor wishes.

They complained formally last month to the papal nuncio, the Vatican representative in Washington, D.C., and have alerted Los Angeles Archbishop Jose Gomez, the head of the American bishops’ conference, along with a cardinal in Rome who oversees clergy issues and charitable foundations for Pope Francis.

A spokeswoman said the bishop was on vacation for the month and unavailable for an interview. His representatives denied he or the church acted improperly, but declined to answer many questions about the situation, with the spokeswoman, Tracey Kincaid, saying the diocese “does not comment on internal processes.”

Orange County has to remain off for 14 consecutive days in order to receive the green light to reopen all schools for in-person learning, and Sunday would mark the halfway point.

The situation unfolding in Orange County might be a harbinger for other dioceses. At a time when generational shifts and the fallout of the abuse scandal have made Catholics more willing than ever to question church authorities, COVID-19 is forcing controversial decisions on bishops. A Georgetown University survey of 116 American bishops published last month found that as a result of declining revenues in the pandemic, nearly a quarter were considering closing parishes and 45% either had closed elementary schools or were considering doing so.

The church in California has added financial pressure. A state law that took effect in January allowed a three-year window for the filing of sexual abuse claims previously barred by statutes of limitation. Lawsuits are already piling up against church organizations across the state.

The most striking part of the Orange County conflict may be that the bishop’s opponents are not church critics, but devout insiders.

Two forced off the charity board by the bishop, the real estate developer Rand Sperry and Dr. Jacqueline DuPont, chief executive of assisted living companies, have received awards from the diocese for “exemplary business integrity,” and DuPont co-chaired the gala dedication last summer of Vann’s crown jewel, a gleaming new $130-million cathedral complex in Garden Grove. The board member who wrote the Vatican complaint, Tustin attorney Don Hunsberger, was honored in 2019 as Orange County’s Catholic Man of the Year.

“Not one of my brethren among the board of Directors of The Orange Catholic Foundation has ever found herself or himself in the position of having to question the actions of our Ordinary in a manner such as this,” Hunsberger, the former board secretary, wrote to the nuncio July 2, using the ecclesiastical term for bishop. “Each of us has suffered under the weight of having to make this decision.”

Most of the directors forced off the 18-member board did not return messages and those who did declined interview requests. This story is based on emails, memos and other internal diocese and foundation records as well as the accounts of people familiar with the dispute who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

California was in its first day of the COVID shutdown when the chief financial officer of the diocese approached the Orange Catholic Foundation and said the bishop needed a lot of money and quickly. CFO Elizabeth Jensen said the school system was short $8 million and parishes $4 million, according to correspondence reviewed by The Times and interviews with people familiar with the conversation.

In a follow-up email March 23 to foundation Chairman Stephen Muzzy, a Trabuco Canyon real estate and private equity investor, the CFO wrote that nine parishes lacked “enough cash to meet near-term basic expenses.” Parents in poor areas and “even some in South County” were unable to make tuition payments, she said.

“I believe the situation is getting to the point of being grave, which motivated me, on behalf of Bishop Vann, to ask for the resources from OCF for which I truly consider to be real needs,” Jensen wrote.

Money the foundation provided might be repaid down the road, she said, but “there is no guarantee. We are all in uncharted waters.”

The emergency funding request, which the board ultimately declined, was unprecedented in the foundation’s history. The nonprofit had been set up 20 years before in the midst of another crisis: Revelations that priests had sexually abused children and their superiors had covered it up. As the abuse crisis swept the country in the late 1990s and early 2000s, big donors cut back on their giving. Many said they did not trust church leaders who had covered up molestation and did not want their money going to pay legal bills or million-dollar settlements with abuse victims.

Church leadership devised a solution embraced by many dioceses: Independent foundations that benefited Catholic causes, but were outside the control of the bishop. In some cases, dioceses moved existing church assets into the new nonprofits, making them beyond the reach of plaintiffs and other creditors should the local church fall into bankruptcy.

Retired Laguna Niguel banker Jim Tecca, who chaired the foundation years before the current dispute, explained the dynamic between the diocese and the foundation in a way fitting for property-mad Orange County.

“If you are an investor in a piece of real estate, you set up a corporation rather than doing it yourself. In case there are lawsuits ... personal assets are not at risk,” Tecca said.

By the time then-Bishop Tod Brown signed a $100-million settlement with 90 victims in 2005, the independent foundation was already up and running. It grew into a prestigious and trusted organization that doled out millions in grants annually and held endowment money for parishes and institutions including Mater Dei and Santa Margarita high schools.

Its annual Conference on Business and Ethics drew high-profile speakers such as actress Patricia Heaton and Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for Catholic schools while its estate planning seminars primed wealthy parishioners to leave money or property to the foundation. The average bequest to the nonprofit was a startling $867,000, according to recent marketing materials.

Critical to its success, supporters say, was donors’ view of the foundation as entirely Catholic yet independent from the hierarchy, or as its mission statement states, “an autonomous, pious foundation that works with members of our Diocese ... following each donor’s intent.”

Donors were assured that contributions will be used for the purposes they specified, whether seminarian training, care of elderly priests, parishes in poor neighborhoods, scholarships at a particular grammar school or purchase of the cathedral organ.

“We told every single donor that same mission statement,” said Susan Strader, a board member from Newport Beach who with her husband, real estate developer Tim, chaired the fundraising campaign to complete the cathedral complex. “Their money could go to candlesticks, lectionaries, stations of the cross, buildings, classrooms. There was no money that was just able to be moved out of that donor intent.”

A volunteer board dominated by lay business people governed the foundation, and its promotional materials laid out the limits of the bishop’s influence: “The Bishop of Orange is one of the voting members of the board of directors but is not the chairman.”

Tecca, the former board chair, could not recall a single legal or ethical dispute during his tenure, he said, adding, “The reason is we did what the donor said. Exactly. No question.”

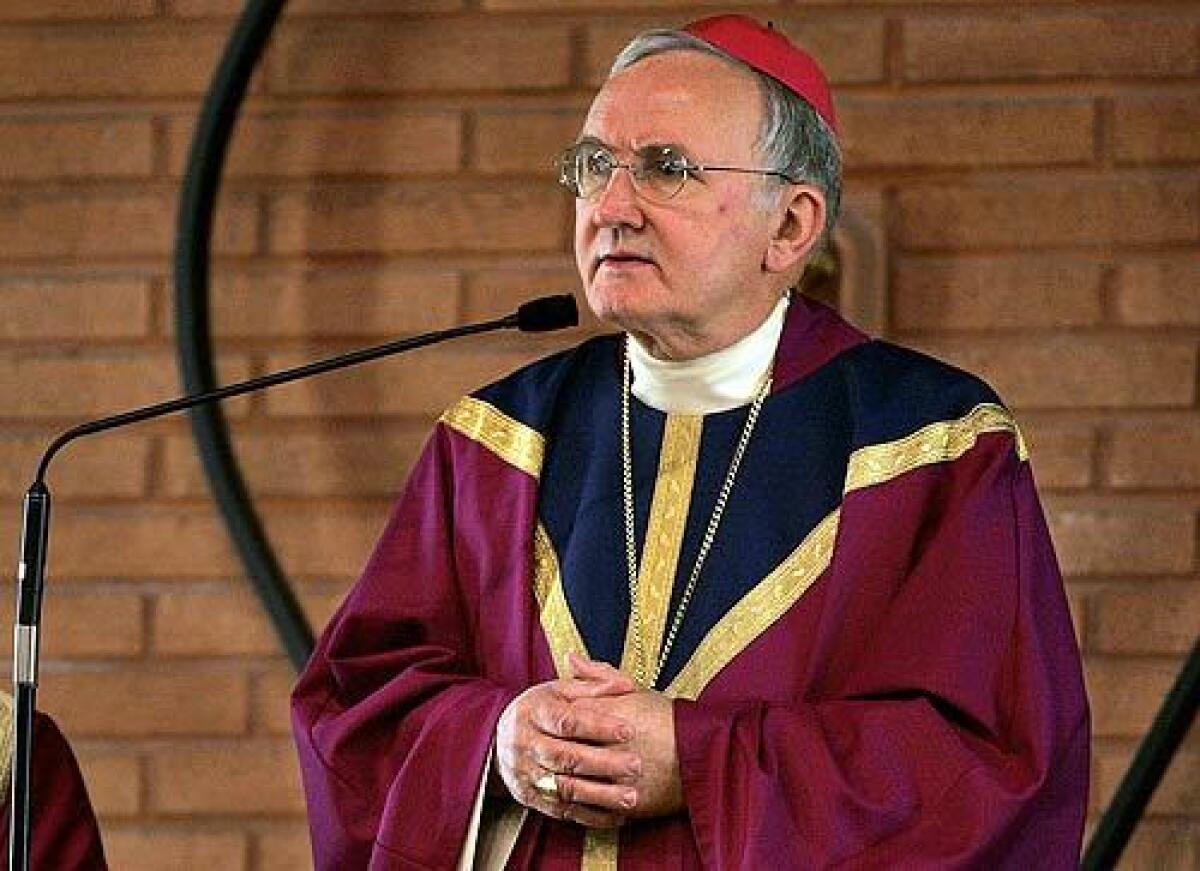

Vann, a 69-year-old native of Illinois, was installed as bishop in 2012, a year after the diocese bought televangelist Robert H. Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral out of bankruptcy for $57 million. The 34-acre property needed extensive renovations that topped $72 million.

The cathedral had been open less than a year when the coronavirus hit. When the diocese told the foundation board in a March 19 call that it was in need of $12 million, the foundation had assets of about $45 million.

People with knowledge of the call said Jensen, the diocesan CFO, asked the foundation for the entire amount. Through a diocesan attorney, she said she never asked for $12 million and was only laying out the scope of the problem.

In a written request two days later, she identified more than $2.6 million in specific foundation accounts she wanted turned over to the diocese. She noted that the board’s funding decision “should respect the intent of the donors.”

Much of foundation money was in endowments that paid a small percentage of their value to dedicated causes annually. State law requires charities to be “prudent” when disbursing endowment money and to follow any donor instructions. The foundation’s agreements capped the amount at 5% a year. Yet Jensen was requesting 25% of two funds and 50% of another, according to her written request.

In a statement provided by the diocesan lawyer, Jensen said that when she asked for the money, “I had no specific knowledge of the particular restrictions in each of the donor agreements. For that reason, I emphasized that any limitations imposed by donors must be followed.”

In a series of phone calls and emails, board members told church officials that while they wanted to help, the law wouldn’t allow it.

“Right now you, you feel the Board’s hands are tied and cannot grant any funds for the foreseeable future,” Jensen summarized in a March 25 email that prompted the board chair, Muzzy, to reply, “I am shocked at what I perceive to be the tone of your email — that the OCF does not want to help the [bishop.]”

In a three-page letter later that day, Muzzy wrote that on the advice of its lawyers, the board was denying the diocesan request for emergency funds. He attached a copy of the state law governing endowments.

The board, he wrote, “cannot breach its fiduciary duties and statutory requirements as custodian of endowment funds. To do so would be a breach of every duty we have to our donors ...”

The bishop had other potential sources of money. The diocese annual financial report showed that as of July 2019, the diocese had $195 million in net assets with $37 million of that held in “cash and cash equivalents.” Parishes, schools and other organizations also received loans of more than $18 million from the federal Paycheck Protection Program, a government database indicates.

Still, in the following weeks, members of the foundation board searched for emergency money for the diocese, including soliciting donations from long-time benefactors. They handed over $1.4 million in April, according to foundation records The Times reviewed.

The money did not pacify Vann. On a June Zoom meeting with board members, he said he saw the new funds as evidence that Suzanne Nunn, a longtime foundation consultant serving as acting executive director, had lied about whether the nonprofit had money for the diocese, according to sources familiar with the situation who asked not to be named. The sources said Vann told the board to fire her. They refused, telling the bishop’s staff that Nunn served at the board’s pleasure, not his, the sources said.

Nunn declined to comment. After the bishop made his displeasure known, she decided to leave the foundation anyhow and the board was scheduled to finalize her severance agreement at a meeting June 19.

Early that morning, Vann informed the board by FedEx letters that he had decided “to remove all the current elected members” of the board. He said the board had failed to achieve goals he set out for them including establishing a strategic plan and hiring a permanent executive director, despite repeated requests.

“[S]peaking as a father to his family, there has been a loss of trust and collaboration,” he wrote, adding, “While I had hoped to avoid this outcome, I have come to believe that this is necessary and in the best interests of OCF and its mission at this particular time in our history.”

He thanked them for their service and signed the letter “Yours in Christ.”

The same day, a new chair appointed by Vann, fired Nunn.

The dismissed board, which included a parish priest from San Clemente and a 74-year-old nun who worked at the cathedral, was stunned. One former director remarked, “I feel like I’ve been fired by God,” according to sources familiar with the board’s response.

As it often does, the shock gave way to lawyers. Attorneys pored over church law and corporate governance documents, and argued that the bishop had violated state corporate law, according to emails and memos reviewed by The Times. The foundation’s bylaws allowed a majority of the board to remove a director for any reason, but the bishop was limited to removing a director only for a spiritual failing, such as excommunication or causing a public scandal, or for acting against the objectives of the foundation.

Three board members, Muzzy, Hunsberger and Newport Beach finance executive Ryan Kerrigan, told Vann in a July 2 letter that he lacked legal authority to fire the directors and urged him to reconsider.

“What have we done to deserve such arbitrary, judgmental treatment,” they wrote, copying Gomez, the head of the L.A. archdiocese, and the papal nuncio, Archbishop Christophe Pierre, and another Vatican official, Cardinal Benjamin Stella.

A letter to Pierre the same day begged apologies for “sending this letter on plain white paper.”

“We have been locked out of the offices of the Foundation by order of our Ordinary, so we do not have access to stationery worthy of the recipient of this missive,” Hunsberger wrote on behalf of the fired board.

An accompanying memo prepared with a lawyer for the foundation warned of dire potential legal consequences. It charged that the bishop had opened the diocese up to suits by the ousted directors for their “illegal” removal and by Nunn for being dismissed “based on her refusal to allow illegal actions.” Additionally, the memo asserted, donors could file breach of contract suits and plaintiffs’ attorneys in the new clergy abuse suits could go after foundation money.

The bishop responded July 28, telling the three board members that the directors’ removal “was strictly in accord with the OCF Bylaws as well as canon and civil law, as I confirmed in advance, to ensure the continuing appropriate separation of OCF and the Diocese.”

‘I can’t imagine a bishop being that naive to think he can get away with that and not alienate donors, big and small’

— Charles Zech, an expert on the Catholic Church’s finances and management

A diocesan lawyer said in a statement that the foundation assets remained off limits from those with legal claims against the church.

“[T]here can be no suggestion that ... any creditor of the [diocese] can pierce the corporate veil and tap into the assets of OCF,” the lawyer wrote.

So far the Vatican has not weighed in publicly. The nuncio did not respond to messages. A spokeswoman for Gomez did not answer questions about the archbishop’s response to the conflict in Orange, but noted in an email that he “has no day-to-day administrative oversight of the Diocese of Orange.”

A member of the old board, Strader, was reappointed to the new board. Asked about her former colleagues’ complaint, she said the bishop “is the Ordinary of the diocese so they don’t really have a leg to stand on.”

Since the changeover, the new board has not disbursed more than 5% from any endowment, according to a diocesan lawyer.

The diocese’s most important donor, Timothy Busch, an Irvine entrepreneur who co-founded JSerra High School in San Juan Capistrano, gave heavily to the new cathedral and gifted more than $15 million to Catholic University, declined to comment.

“I was not involved on that board or the decision,” he said in a text, adding, “Thank you for caring about church governance.”

Villanova Professor Emeritus Charles Zech, an expert on the Catholic Church’s finances and management, said that he was unaware of a similar dispute between a bishop and foundation, and called the firings “outrageous.”

“I can’t imagine a bishop being that naive to think he can get away with that and not alienate donors, big and small,” Zech said.

Harriet Ryan is a staff writer with the Los Angeles Times.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.