Text messages reconstruct copter crash that killed Kobe Bryant, 8 others

The text messages followed Kobe Bryant’s helicopter on a quiet Sunday morning five months ago.

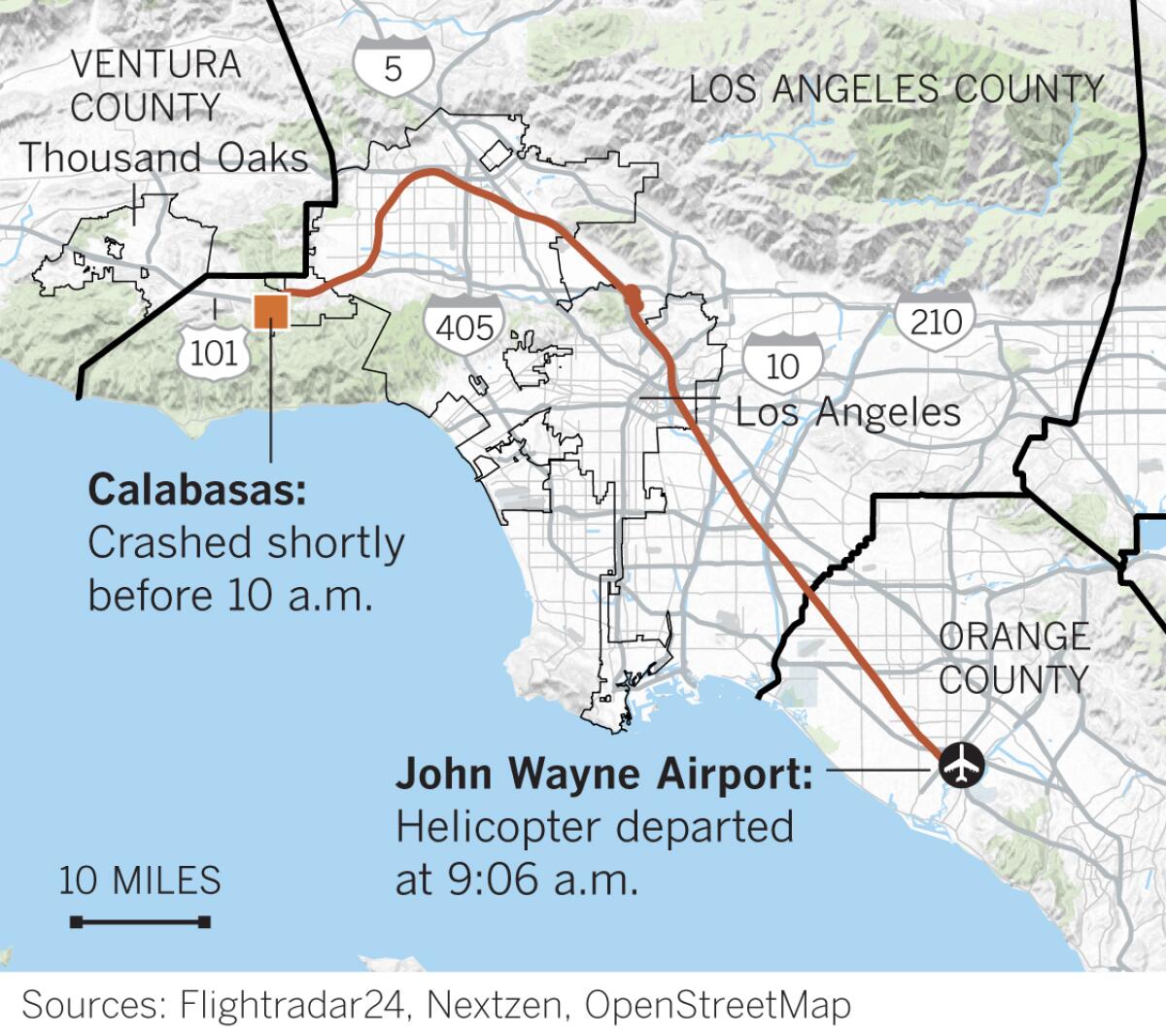

“Wheels up,” the broker who arranged the flight messaged as the Sikorsky S-76B left John Wayne Airport in Santa Ana at 9:06 a.m.

Veteran pilot Ara Zobayan would transport Bryant, a Newport Coast resident, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and six others on their way to basketball games at the Mamba Sports Academy in Thousand Oaks. Zobayan, a Huntington Beach resident, was Bryant’s favorite pilot. The retired Lakers star called him “Mr. Pilot Man.”

“Just started raining lightly here,” one of Bryant’s drivers messaged from Camarillo Airport, the helicopter’s destination, at 9:33 a.m.

The same group had flown without incident to the same destination a day earlier — and Zobayan flew Bryant on the route at least 10 times last year.

A text message thread among the broker, charter company and drivers accompanied each flight. The smallest details mattered, like reminding the drivers that Bryant’s backpack was stashed in the back of the blue and white helicopter.

The pilot of Kobe Bryant’s helicopter dismissed concerns about the weather before the crash that killed Bryant and eight others, NTSB documents show.

“Land?” another broker employee texted at 9:48 a.m., three minutes after the flight had been scheduled to arrive.

“Not yet,” the driver responded a minute later.

Thirteen minutes of silence on the thread masked growing alarm.

“Ara, you okay,” the broker messaged at 10:02 a.m.

The pilot didn’t respond.

The text messages are among more than 1,700 pages of interview transcripts, emails, studies and pictures released by the National Transportation Safety Board on June 17 that document the flight that slammed into a fog-covered hillside in Calabasas on Jan. 26, killing all nine people on board. A previous report by the NTSB didn’t find any engine or mechanical failure.

The new batch of records doesn’t draw any conclusions about the accident. But they provide a minute-by-minute account of Bryant’s last flight from Zobayan’s girlfriend, mechanics who worked on the S-76B, air traffic controllers, pilots, employees of the charter company and broker, a personal assistant for the family and eyewitnesses to the crash.

The previous night, Patti Taylor from OC Helicopters, the broker that arranged Bryant’s flights and ground transportation, reviewed the plan.

“Weather look ok tomorrow?” she messaged the group.

“Just checked and not the best day tomorrow but it is not as bad as today,” Zobayan responded.

The departure had moved from 9:45 a.m. to 9 a.m. so Bryant could watch another team play. They would return around 3 p.m.

“Advised weather could be issue …” Taylor added.

“Copy,” Zobayan said. “Will advise on weather early morning.”

Tess Davidson, Zobayan’s girlfriend of seven years, told investigators that he reviewed weather through an app on his iPad called ForeFlight the night before each flight and didn’t hesitate to cancel a charter if conditions weren’t right.

“He would not be pressured into flying,” she said.

Island Express cancelled 150 flights because of weather last year, according to investigators. Some of them involved high-profile clients such as Kylie Jenner and Clippers star Kawhi Leonard. In the two days before the accident, weather forced the cancellation of 13 flights. Bryant wasn’t immune from weather-related scheduling issues, either.

“There was often times where perhaps we had to fly [Bryant] one way but couldn’t fly him back due to weather that came in or had to cancel or had to delay it,” Taylor, the broker, told investigators. “Now, make no mistake, he didn’t like being told no, but we told him no.”

She echoed Zobayan’s girlfriend: “Ara could never be pressured to fly if it wasn’t correct.”

Kurt Deetz, a former Island Express pilot who had flown Bryant, told investigators Bryant left weather issues to the pilot because “he assumed you’re doing your job.”

Bryant had an unusual level of comfort with Zobayan. In interviews with investigators, colleagues described the chief pilot for Island Express as personable, detail-oriented and thoughtful enough to buy a new drill for one of the company’s mechanics as a surprise and diapers for the child of another employee. He woke up around 6 a.m. each day without the aid of an alarm clock, rarely drank alcohol and had more than 8,500 hours of flight time. Though other pilots had been cleared to fly the Bryant family, they wanted Zobayan.

The pilot regaled colleagues with stories of flying Bryant around Southern California. Actor Lorenzo Lamas, who also worked as an Island Express pilot, recalled Zobayan telling him about transporting the Bryant family to San Bernardino International Airport on Thanksgiving. Much to Zobayan’s surprise, Bryant returned to the helicopter a few minutes after landing. He had forgotten the stuffing. Zobayan flew him back to John Wayne Airport to collect the side dish.

Whitney Bagge, vice president for Island Express, told investigators the relationship between Zobayan and Bryant became a friendship. Taylor said Bryant trusted Zobayan “with his girls and family, which was paramount to him” and the interactions between pilot and client were “very warm and friendly and joking.”

Bryant’s widow, Vanessa, sued Island Express and Zobayan’s estate in Los Angeles County Superior Court in February, alleging the company “permitted a flight with full knowledge that the subject helicopter was flying into unsafe weather conditions.” Surviving members of the three other families who lost members in the accident have also filed lawsuits. An attorney for the company has called the crash a “tragic accident.”

At 7:30 a.m. on Jan. 26, Zobayan texted the group that the weather was “looking ok.” Taylor followed up about the weather 50 minutes later. Zobayan responded, “Should be OK.” Ric Webb, the OC Helicopters owner, chimed in: “I Agree.”

Zobayan flew the S-76B from Long Beach to John Wayne Airport, landed at 8:39 a.m., then reviewed the upcoming flight with Webb on the ForeFlight app.

“He swiped his finger that he was going to go east and north of the clouds,” Webb told investigators. “At no time did he imply or show that he was going to go in the clouds.”

The NTSB’s operational factors and human performance report said, “Evidence of the accident pilot receiving a weather briefing from an approved source could not be determined.”

The eight passengers arrived at the Atlantic Aviation ramp: Bryant and Gianna; Orange Coast College baseball coach John Altobelli, his wife, Keri, and their daughter, Alyssa; Sarah Chester and her daughter, Payton; and Christina Mauser. Gianna, Alyssa and Payton were teammates. Mauser, an Edison High School alumna, was an assistant coach.

The helicopter followed the 5 Freeway toward Los Angeles, circled Glendale for 12 minutes, then flew along the 101 Freeway toward Thousand Oaks.

At 9:44 a.m., Zobayan told the air traffic controller he was west of Van Nuys and planned to climb above the layer of clouds.

“Uh, we climbing to 4,000,” he said a minute later.

“And then what are you gonna do when you get to altitude,” the controller asked.

There was no response. The controller asked several more times. No response.

The helicopter crashed into a hillside amid dense fog near Las Virgenes Road and Willow Glen Street at 9:45 a.m.

A witness emailed the NTSB that “there was zero visibility past the point where I saw it disappear into the low cloud at the trailhead” and she “found it peculiar they flew directly into heavy clouds so close to hills …”

Another witness emailed the agency: “We heard the helicopter flying normally, but couldn’t really see it because it was extremely foggy and low clouds. I was thinking to myself of why a helicopter would be flying so low in very bad weather conditions. Then, all of a sudden, we heard a large BOOM.”

The NTSB’s aircraft performance study said the helicopter banked left and away from the 101 while communicating with the controller. When Zobayan said the helicopter was climbing, it was actually descending. According to the study, the pilot “could have misperceived both pitch and roll angles.”

“When a pilot misperceives altitude and acceleration it is known as the ‘somatogravic illusion’ and can cause spatial disorientation,” the report said. In other words, acceleration could cause a pilot to sense his vehicle was climbing when it was not.

At 9:49 a.m., Taylor, the broker, asked Bagge, the Island Express vice president, to check on the helicopter’s location. Its tracking had stopped at 9:45 a.m. on Spidertracks, the application the company used to follow its aircraft.

“Patti was extremely concerned,” Webb told investigators. “The drivers saying, ‘Is the helicopter there? Where is the helicopter?’”

Zobayan would usually text “landed” to the group when the helicopter arrived, followed by a driver messaging “passengers on board” and another text when they reached the final destination.

The new tattoos on Vanessa Bryant’s neck and wrist feature the words of her late husband, Kobe, and their late daughter, Gianna.

The company tried to raise Zobayan on the radio and his phone. No answer.

Bagge took a screenshot of the flight circling over Glendale. She figured that’s why it was late.

“It looks like he got held up in airspace or Kobe wanted to look at something over there, which wasn’t uncommon,” she told investigators.

Bagge kept refreshing the tracker. It didn’t change. She prayed the tracker was just broken, but told Angel Perez, a ground operations manager for the company, to pull its emergency response manual.

“Angel attempted calling Ara and [director of operations] Garret [Dalton] a few times with no success and both went to voicemail, I text him back right away, ‘Go to the Emergency Response Manual now,’” Bagge wrote in an account provided to the NTSB.

Camarillo Airport hadn’t seen the helicopter.

They reached Dalton, who drove toward Calabasas.

Around 10 a.m., Zobayan’s girlfriend woke up and followed her morning routine of texting him. The message didn’t go through.

At 10:22 a.m., following one of the procedures in the manual, a different Island Express helicopter was ordered to the last known location of the missing aircraft. But five minutes later, they told the helicopter to turn around.

A crash had been confirmed in the same area where the tracker stopped.

Nathan Fenno is a staff writer with the Los Angeles Times.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.