Unsheltered, Part 2: Cities take to streets — and, lately, shelters — to tackle homelessness. Is it enough?

Editor’s note: This is the second article of Unsheltered, a five-part series examining homelessness in the cities of Costa Mesa, Fountain Valley, Huntington Beach, Laguna Beach and Newport Beach. Though many private organizations and various levels of government are involved in the search for solutions, the series looks specifically at the problem in local cities, what they are doing about it and what more might be done. In this article, we examine what local governments are doing to address homelessness.

The chilly winter air rushed in as Mike Brumbaugh opened the door of his patrol vehicle.

It was a drab and dreary day in late February — so socked in with fog that even a Londoner would think twice before venturing into the suffocating gray.

The haze didn’t faze Brumbaugh as he strode toward a man in a wheelchair near a gas station off Harbor Boulevard in Costa Mesa.

“How’s it going, man?” Brumbaugh said in greeting.

The man — like many of Costa Mesa’s homeless — was a familiar sight for Brumbaugh.

During his regular patrols throughout the city, Brumbaugh, a city senior code enforcement officer, meets with the local homeless population and responds to complaints or concerns from residents and businesses.

His goal isn’t to hassle those he finds on the streets — it’s to talk to them, get to know them and, hopefully, find a way to help them.

It’s not an easy task.

“What a lot of people don’t realize is this isn’t just a job,” Brumbaugh said. “It does get emotional sometimes because you get to know people out here, and you know some you can help and some you can’t.”

Brumbaugh had spoken with this particular man before, even given him a requested bus pass.

Yet, here he was.

After chatting a bit, Brumbaugh turned back toward his vehicle.

“Be careful out here, all right?” he said.

After years of performing such a ritual, Brumbaugh has made his share of memories — some good, others less so.

It comes with the territory when you’re on the front lines of the battle against homelessness.

“Could you imagine if this was your daughter or your son out here?” he said. “Could you imagine being that parent at home, wondering? It’s heartbreaking in a lot of ways. … You want to try to make a difference and you can’t always do that. You have to know that upfront.”

“I wish there was nobody on the street, but you have to realize too that, like in life, you can help those that want help,” he added. “And you still try to help those that are maybe a little more resistant in the hopes that someday they go, ‘OK, all right, I’m ready,’ because that does happen.”

The first of a five-part series examines some of the major factors that contribute to local homelessness, along with who and where homeless people are.

Brumbaugh’s mission is far from solitary. In Costa Mesa, he’s part of the city’s Network for Homeless Solutions — a collaboration of city staff, local churches, nonprofits, private organizations and volunteers formed to address local homelessness.

Similarly tasked resource officers pound the pavement in other cities, looking to contact homeless people and connect them with services and other assistance.

Earlier in February, Tony Yim — a Newport Beach Police Department homeless liaison officer — approached a tarp at the base of the Balboa Pier.

“Hello, it’s Tony,” he called out, as if standing outside a neighbor’s door.

He exchanged words with one of the tent’s inhabitants, but no one emerged.

As Yim drives around the city, he checks in with local homeless people — largely around the Newport and Balboa piers and a local bus depot — and offers them a lift to where they can access services.

The bus station, on Avocado Avenue, was cleared of a homeless encampment in September as Newport police began trespassing enforcement requested by the Orange County Transportation Authority.

If Yim’s job has taught him anything, it’s that each homeless person in Newport Beach is an individual. All have their own stories, needs and fears.

As Yim is fond of saying, “If you’ve met one homeless person, you’ve met one homeless person.”

In February, Yim came across Tom Gallenkamp, who had been staying under the Balboa Pier.

Gallenkamp, 60 at the time, is a local native who worked at an Orange Julius on Main Street as a teenager. These days, he does mostly handyman work.

He said he used to live in an apartment on 12th Street but couldn’t afford it after his landlord raised the rent.

He takes it in stride, though. After all, he said, he’s been miserable before while housed.

However, his time staying near the pier or on a friend’s couch has given him some perspective.

“How many people are two or three paychecks from being homeless themselves?” he said.

Commitments

As homelessness in California has exploded, cities throughout Orange County have wrestled with how best to tackle it.

While nonprofits, private-sector and faith-based groups have long been important cogs in the effort to address homelessness, local governments have found themselves increasingly under pressure in recent years to do their “fair share.”

Cities’ responses have included carving out bigger chunks of their budgets for homeless services or adding new homelessness-focused staff positions to their payrolls.

Another popular strategy has been convening task forces. Costa Mesa created one in 2011, Huntington Beach formed one in 2015 and Newport Beach did likewise in 2019.

Proponents say those panels enable cities to not only familiarize themselves with their homeless communities but also tailor their efforts to provide the greatest benefit.

“It really helps us build those relationships with the individual, because they’re seeing that we’re here to help them,” said Stacy Lumley, Costa Mesa’s neighborhood improvement manager. “We’re not here to, as they would think, get them in trouble. ... We’re here to help them try to end their homelessness.”

Huntington Beach City Councilwoman Kim Carr said Surf City’s task force — consisting of two full-time police officers, one program coordinator and four case managers — has “helped over 262 individuals get off the streets and reunited over 70 individuals with their families.”

“Huntington Beach is committed to being a part of the solution and protecting our residents’ quality of life,” Carr said.

However, until recently, cities have been more reluctant to take another, more concrete step: opening local homeless shelters.

Shelter question

Locally, Laguna Beach was ahead of the pack on homeless shelters. The city’s facility, called the Alternative Sleeping Location, opened in November 2009. The ASL, located on Laguna Canyon Road, has 40 beds available for homeless people, as well as five more on reserve for the city Police Department to provide to people in need.

The shelter also recently began offering a daytime drop-in program giving homeless people an opportunity to shower, do laundry, send mail, eat a meal and apply for housing and other social services between 10 a.m. and 1 p.m.

As Laguna Mayor Bob Whalen pointed out, “For years and years, we’ve been the only city in south [Orange] County that has provided a shelter.”

“We’re proud of what we’ve done in terms of sheltering services … we think we continue to be a model for that,” Whalen said in April. “But [we] do look for others to carry their fair share at this point because we feel that we, for years, have probably … been taking more.”

While other South County cities have largely balked at opening their doors to shelters, some in the central coastal area have taken major steps toward that end in the past year.

The Costa Mesa City Council agreed in January 2019 to move ahead with a 50-bed shelter initially located at Lighthouse Church of the Nazarene in the city’s Westside and eventually slated for a property near John Wayne Airport. The shelter opened at the church in April.

Costa Mesa, Orange County and the cities of Anaheim and Orange were named in a 2018 federal lawsuit filed on behalf of homeless people cleared from a former encampment along the Santa Ana River.

The lawsuit alleged that the cities had taken actions that effectively forced homeless people to move to the riverbed and that the county’s subsequent move to clear the area would push that population back into the surrounding cities without a plan to provide adequate shelter and housing.

Costa Mesa’s shelter was a primary component of the city’s agreement to settle the riverbed lawsuit in March.

Costa Mesa Mayor Pro Tem John Stephens said the legal action played a major role in prodding the city in the shelter direction — as did U.S. District Judge David Carter, who oversaw the case.

“He made clear in no uncertain terms … that he would not put up with what he called ‘dumping,’ which is transporting someone who is experiencing homelessness in Costa Mesa or wherever and sending them to another city,” Stephens said.

“He changed the way people thought about that issue and he created some jeopardy for anybody who would do that type of activity.”

Throughout hearings and conferences on the lawsuit, Carter pushed cities to develop more emergency shelter and transitional housing beds — where homeless people could find refuge and access services and support to help them eventually move into more-permanent housing.

He also toured the river encampment and was on hand when Costa Mesa officially opened its shelter April 5.

“This is an extraordinary journey,” Carter said during the opening ceremony at Lighthouse Church. “It’s a journey that many communities are starting to take.”

Huntington Beach and Newport Beach also have started on that path.

Huntington City Council members in April approved the purchase of a warehouse building at 15311 Pipeline Lane with the idea of developing a 75- to 90-bed homeless shelter there. However, those plans hit a roadblock because of a lawsuit filed by residents, property owners and business owners who claimed the site can be used only for industrial purposes.

The city later agreed to sell that property — taking a nearly $80,000 loss in the process — and is continuing to search for a suitable location, possibly a portion of the property in Costa Mesa that is slated for that city’s long-term shelter.

“None of us like the spot that we’re in, but we know that a tough decision is what’s necessary in order to make sure that this doesn’t spiral out of control, and we end up looking like the Santa Ana River trail at some point,” Huntington Councilman Patrick Brenden said in April.

Newport Beach also has been looking at potential shelter sites in recent months. But its planning has met with threats of legal action from residents, especially over the possibility of a shelter at the city public works yard at 592 Superior Ave.

“We’ve done a lot, but it’s clearly not enough,” Newport Mayor Will O’Neill, who chairs the city’s homelessness task force, said in September. “We need to move quickly but not so quickly that we make decisions that are bad and stain us for years to come.”

Whatever a city’s reason for embracing a shelter, the domino effect reflects an evolution in how some local leaders view homelessness — a shift away from the perspective that a city’s responsibility extends only to its own borders.

“It’s not a victory to move a homeless person from Costa Mesa to Huntington Beach or Huntington Beach to Costa Mesa or from Costa Mesa to Santa Ana or from Santa Ana to Fountain Valley,” Costa Mesa’s Stephens said. “The days of just kind of moving our problem from one city to the other need to be over.”

Becks Heyhoe, director of United to End Homelessness for Orange County United Way, believes the lawsuit over the river encampment sparked a seismic shift in the way area cities look at homelessness — in part by uprooting the county’s reputation as an exclusive wealthy enclave.

“Homelessness wasn’t something [people] thought of when they thought of Orange County,” she said.

The issue at the riverbed and subsequent legal action, she added, “maybe shattered some illusions that the rest of the country had about life in Orange County.”

Looking ahead, elected officials throughout the region emphasize the need for collaboration across municipal boundaries to build on the efforts of individual cities.

However, a potentially major obstacle to that goal is — as always — money.

As the Costa Mesa city manager’s office put it: “The primary obstacle to a comprehensive solution is county and state inaction toward providing funding to local jurisdictions that are proactively doing their fair share to protect vulnerable individuals and better the public health of their communities. The governor and the county must collaborate with local cities to ensure funding flows to cities that proactively shelter and house homeless individuals.”

“It’s not a victory to move a homeless person from Costa Mesa to Huntington Beach or Huntington Beach to Costa Mesa or from Costa Mesa to Santa Ana or from Santa Ana to Fountain Valley. The days of just kind of moving our problem from one city to the other need to be over.”

— John Stephens, Costa Mesa mayor pro tem

State funding

The state is opening its checkbook for the cause.

California’s latest budget includes $650 million to fund homelessness-related programs in large cities and counties, as well as efforts carried out by regional prevention agencies.

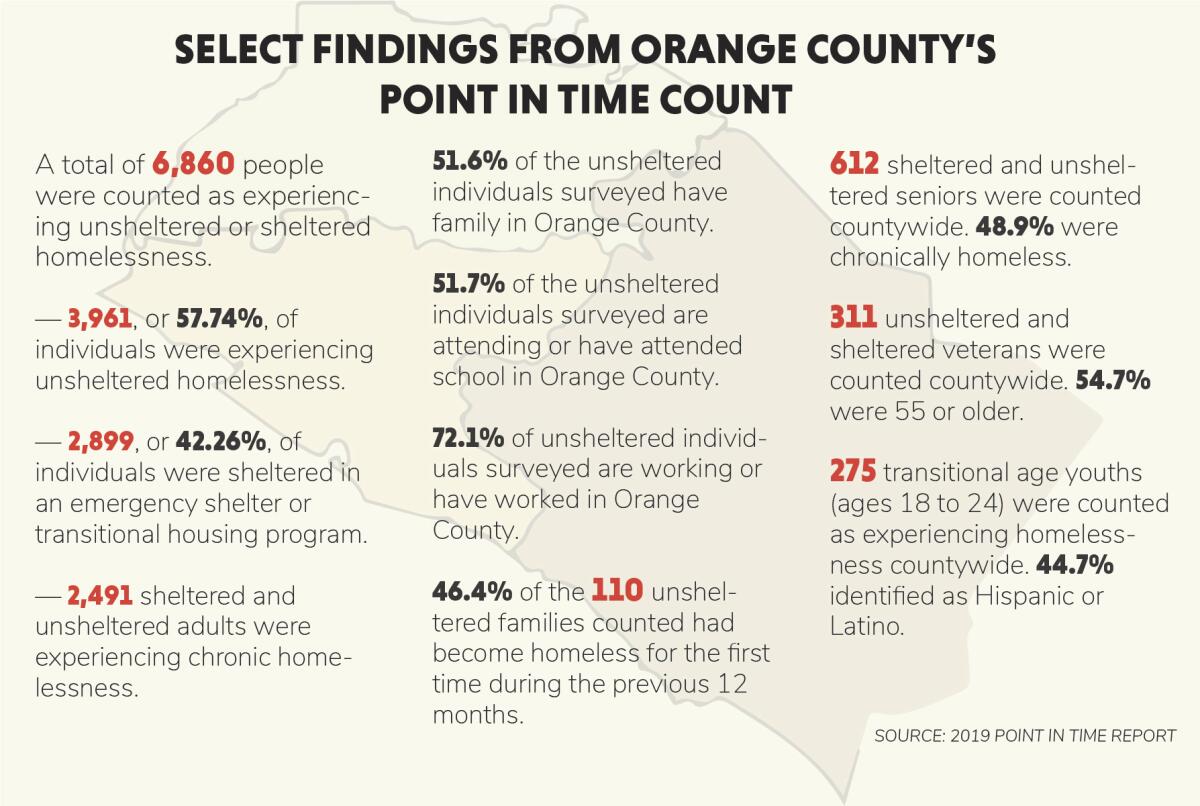

Also budgeted is $2.9 million that will be directed to the Orange County United Way’s United to End Homelessness Welcome Home OC program. That effort provides rental-assistance vouchers to help place homeless veterans — of which 311 were tallied during the most recent Orange County Point in Time count last January — in private apartments.

“I am committed to working with Orange County United Way and our collaborative partners to get every veteran into housing as soon as possible,” said state Assemblywoman Cottie Petrie-Norris (D-Laguna Beach), who secured the funding. “Thanks to our community’s strong commitment and support, Orange County is poised to become the second county in California to end veteran homelessness.”

The budget also includes $2.2 million to vet the possibility of using the 114-acre, state-owned Fairview Developmental Center property at 2501 Harbor Blvd. in Costa Mesa to provide services for the homeless. The center is slated to close, possibly in 2020.

“These men and women are our hidden neighbors; they come from all over Orange County and need shelter and medical care in order to find stability and hope,” said Assemblywoman Sharon Quirk-Silva (D-Fullerton), who proposed the concept.

The Costa Mesa City Council came out against a proposal in 2018 to use Fairview as an emergency homeless shelter. It recently decided to form a committee to communicate with state and county officials and advise the council about the facility’s future.

‘Housing is really the key’

Another broader effort is the Orange County Housing Finance Trust, a joint county-cities authority formed in 2019 to secure and allocate funding for affordable and supportive housing projects.

Advocates have said permanent supportive housing — affordable units that include resources designed to keep people housed and connect them with necessary services — is vital to prepare the chronically homeless for long-term success.

An example of that model can be seen in Newport Beach, where the Cove Apartments, a 12-unit complex that serves formerly homeless veterans and low-income senior citizens, opened in 2018.

Helen Cameron, community outreach director at Jamboree Housing Corp. — an Irvine-based developer of affordable and supportive housing — said it’s good that cities are looking to open homeless shelters, but “you can’t have people living in a shelter all their lives.”

“Housing creates a stable foundation for work and quality of life,” she said. “A shelter doesn’t provide that environment. A shelter should not be a destination.”

Advocates say development of robust permanent supportive housing should be the next major item on the county’s homeless to-do list.

“It will take brave elected officials to commit to doing that and moving that forward in their communities,” Heyhoe said.

Dawn Price, executive director of Friendship Shelter, the nonprofit that operates the ASL in Laguna Beach, said “we have had a lot of problem-solving this year. … Regionally, communities have stepped up and established shelters.”

But, she said, “housing is really the key.”

“We don’t think our way out of this problem,” Price said. “We don’t organize our way out of this problem. We certainly don’t argue our way out of this problem. The problem is homelessness and the answer is housing. It really is that simple.”

Coming in Part 3: What are the obstacles on the road ahead?

Daily Pilot staff writers Lilly Nguyen and Julia Sclafani contributed to this report. Priscella Vega writes for the Los Angeles Times.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.