City Lights: What draws in kids? Fun, engaging fantasy

- Share via

When I was a graduate student in creative writing, my classmates hewed mostly to predictable topics: dating, family bonds, drinking and clubbing.

One day, though, a robust gentleman surprised us by handing out 20 stapled copies of a story he had written for children. Evidently, he was concerned about his success, because along with the story, he submitted a sheet of positive blurbs from kids who had given it a first read.

His story, as I recall, was intriguing — a folk tale of sorts about a tribal boy who discovers a beautiful animal that only his eyes can see, and whose name he can articulate in his head but not say out loud. Thinking the boy has gone mad, his tribe threatens to exile him, and then, well, then my classmate reached the page limit for his submission, leaving us all hanging. Such are fiction workshops.

As I read what he shared, though, I tried to break out of the worldly mind-set that I usually brought to class. Those of us who wrote for peers flaunted our intellect, tying in pop-culture references (one woman crafted a stream-of-consciousness narrative with the 1960s London gangster Reggie Kray as a supporting character) and intricately layering plot points and motivations.

Writing a great complicated book is a challenge, but writing a great simple book may be tougher. Consider this Wikipedia summary of Dr. Seuss’ “The Cat in the Hat”: “The story is 1,629 words in length and uses a vocabulary of only 236 distinct words, of which 54 occur once and 33 twice. Only a single word — another — has three syllables, while 14 have two and the remaining 221 are monosyllabic. The longest words are something and playthings.” Yes, and now consider how much of the book you can recite from memory.

Few authors have left a cultural mark of Seussian proportions, but I encountered dozens of hopefuls at Orange Coast College on Sept. 29 for the Orange County Children’s Book Festival. As dreams go, being a children’s author seems both maddeningly elusive and incredibly simple. After all, if Theodor Geisel could make an enduring classic out of 236 words — somewhat fewer than James Joyce used in “Ulysses” — then that provides a glimmer of hope for anyone who tries.

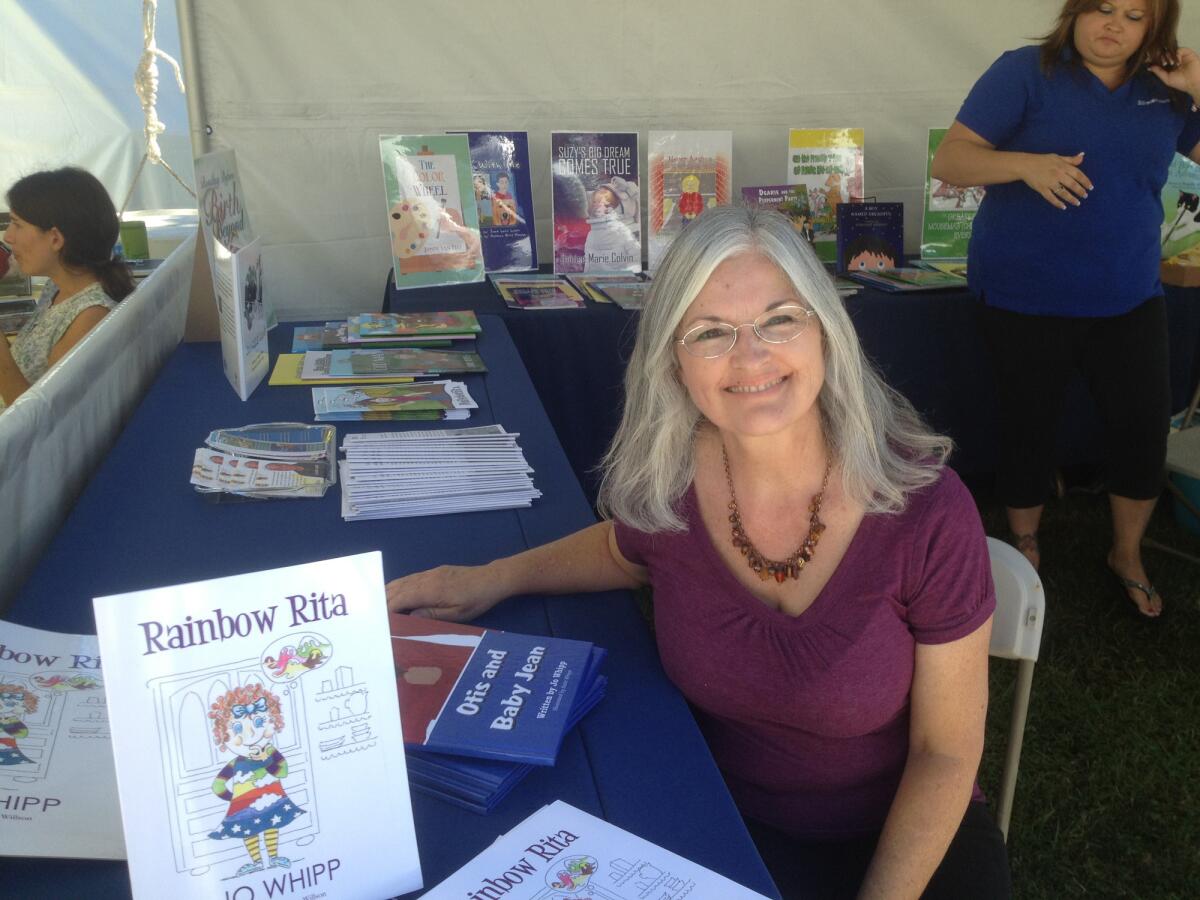

For example, take Jo Whipp. The Paso Robles resident, who occupied one of the booths at OCC, had never participated in a children’s book festival before, and she has just two volumes to her name: “Otis and Baby Jean,” a prose story that she wrote two decades ago and released last year through PublishAmerica, and “Rainbow Rita,” a rhyming book that came out this year from the same publisher.

Whereas my old friend probably had to scrounge to find kids to read his story, Whipp had no shortage of them — she has nine children and home-schooled eight of them. She wrote “Otis and Baby Jean,” about a little girl who steals her older brother’s prized horse statue and then weaves a web of lies when she accidentally breaks it, as a fable for one of her daughters who had a chronic lying problem.

When Whipp ran the story by her kids, they grilled her about some logical plot points: why Baby Jean would take the horse to one place and not another, or whether she could really hide it in her sweater. In terms of their literary tastes, though, she knew them well enough; over the years, they had devoured Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House” series, James Herriot’s children’s books, even Charles Dickens.

So is there a secret to writing for children? Whipp has at least a partial idea.

“I think that the biggest thing that I’ve learned from children is to make it engaging,” she said. “It has to be engaging. For instance, rhyming is a way of engaging because it becomes something that they want to memorize, so that’s a way of engaging them. With the James Herriot books, those books are about animals, and they’re very cute little stories where people come into the animals’ lives and things happen. You want to draw them in. It has to be something they care about, and it has to be done in a fun way.”

She noted that it was harder now to craft a long story for young eyes, with all the electronic stimulation that competes with books. (“Rainbow Rita,” about a girl who overindulges on ice cream, amounts to a mere eight rhymed couplets.)

“They see TV constantly,” Whipp said. “Everything they see, there’s action constantly before them. That’s why it’s important to keep them super-engaged with your writing.”

That word again, engaged. After speaking with Whipp, I tried to remember what held my attention most as a child. Sure, I memorized my share of Seuss, but I had a particular affinity for stories where something huge was at stake — war, romance, a villain’s comeuppance.

My favorite series was “Can You Solve the Mystery?”, in which a pair of 12-year-old sleuths unraveled one case after another. I became disenchanted with Disney’s “Pinocchio” when I read the original Carlo Collodi novel and found that it was longer and meatier.

Oh, and I loved “Harold and the Purple Crayon.” That’s the series about a little boy who wields a massive purple crayon and illustrates places and objects, which become real as soon as he finishes drawing them. On uneventful days in the cubicle, I still fantasize about doing that myself, creating my own mystical worlds while I wait for sources to call back.

Maybe that’s the key: We outgrow those stories from early in life, but our inquisitive nature stays intact. And frankly, if I ever run into my old classmate, I’ll ask if he still has the rest of his story. I want to know how it ends.

No matter the age of the author or reader, that’s always the truest sign of success.

MICHAEL MILLER is the features editor for Times Community News in Orange County. He can be reached at [email protected] or (714) 966-4617.