These groups are helping change climate policy in Orange County

As California begins exploring ways to become carbon neutral to combat the damaging effects of climate change, cities are faced with finding ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

A few Orange County cities have moved forward with plans to decrease their carbon footprints, though advocates contend the county lags behind the rest of the region.

The issue has become all the more crucial following an August report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which called climate change a “code red for humanity” that is already being felt across the world and will only continue to accelerate.

With a strong sense of urgency, a number of area advocacy groups are working to mobilize communities to pressure local officials to enact progressive energy policies, decrease pollution and protect coastlines from erosion.

“In terms of climate readiness and policy, Orange County may be one of the furthest behind in the state,” said Ayn Craciun, policy manager with the local Climate Action Campaign. “Most of Orange County’s 34 cities are doing nothing to adopt the kind of policies that we need to protect vulnerable communities and stop climate pollution.”

Grassroots organizing and community choice energy

Originally founded in 2015 by Nicole Capretz, the Climate Action Campaign’s initial mission was to push San Diego to complete a climate action plan. The nonprofit served as a counterweight to the local fossil fuel industry, which opponents say has an incentive to fight against energy reforms.

The landmark plan made San Diego the largest U.S. city to commit to 100% clean electricity by 2035 and was ultimately approved, largely due to the Climate Action Campaign’s grassroots efforts. The group has used the same approach in Orange County.

Craciun said that after the San Diego plan was approved, Orange County residents and community groups reached out to the nonprofit seeking help to achieve the same thing in their cities. In 2018, there was enough momentum for the campaign to hire a part-time staffer in Orange County.

“Since then, we’ve been working to scale and replicate the same successes that we’ve had in San Diego,” Craciun said.

Over the last few years, the campaign has devoted the majority of its energy to bringing community choice energy, or CCE, to the county. In 2020, Irvine voted to create the Orange County Power Authority, the first CCE in Orange County history. Craciun said the group focused on CCE at first due to the community interest in the program. The authority has four member cities so far, but there are hopes that more cities will join once the program starts providing service in April.

CCE is at the forefront of a California energy revolution. More than 200 cities have adopted the program as climate change continues to devastate with wildfires, drought and high temperatures. The program provides cities with an alternative to major energy providers like Southern California Edison, the energy titan that serves most of the region.

Through a CCE, local governments can retain control of purchasing power, set rates and collect revenue, though the local utility still maintains the electrical grid. CCEs can purchase more renewable energy sources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Irvine, Huntington Beach and Buena Park all recently chose to receive their energy from 100% renewable sources, and Fullerton opted for 70%.

The Climate Action Campaign‘s efforts contributed to Irvine becoming the first city in Orange County to make a pledge of carbon neutrality.

Now, the group will be working toward creating community and political support for building electrification policy to transition away from gas-powered appliances. The nonprofit is doing this work with only two full-time staffers in Orange County — Craciun and Lexi Hernandez, climate equity organizer and advocate.

Craciun said there are many elected officials in the county’s cities who don’t believe in climate science or think that climate action can wait. The campaign’s bottom-up approach to community organizing puts pressure on policymakers to take action.

“There’s huge pent-up demand for climate action in Orange County,” Craciun said. “So we just want to enable people to get involved. Because we know that community is key. It is a key part of our theory of change, which is first we build community will, and then we build political will, and then we win.”

Craciun said that Orange County has surpassed San Diego in some respects — referencing the handful of cities that made the renewable energy pledges and Irvine’s commitment to be carbon neutral by 2030.

Though the county has made some strides, Craciun said that there is much more work to be done. One of the major vehicles for residents to get involved with climate change activism is the campaign’s Orange County Climate Coalition. Formed last year, the coalition serves as an on-ramp to the local climate movement, providing monthly meetings, training and other resources for people to get involved. Craciun said the nonprofit has more than 1,000 volunteers.

“But we’d say we really have just barely begun to scratch the surface in Orange County,” Craciun said.

Now aiming to address building electrification in the county, the group will continue to gather community support by making presentations at PTA meetings, church groups and rotary clubs. Craciun said people care about the climate crisis, but they can tend to think of it as a huge global problem. A major part of messaging is that people can make a difference in their community, which can have huge impacts on the climate crisis.

“The truth is that cities cause the vast majority of our emissions,” Craciun said. “Cities are also where people can have an impact. So an individual needs to focus on their city, which is where they have the most power. We are here to help them do that.”

Critics of the controversial desalination plant say they’ll believe it when they see it.

For Craciun, any successful climate strategy must also include the electrification of residential and commercial buildings. The gas used in buildings for air conditioning, heating, drying clothes and cooking is more than 90% methane, she said. The IPCC report states that eliminating methane is critical to combating climate change. So far, 54 cities and counties in California have adopted building codes that reduce reliance on gas. Craciun said none of those are in Orange County.

Craciun said building electrification is also a critical issue because gas pollution is contributing to environmental inequities. One of the campaign’s goals is to alleviate environmental injustice in the county, where low-income communities suffer health disparities due to pollution.

“The gas pollution that’s causing the climate crisis is also disproportionately harming Orange County’s low-income communities, renters and communities of color because they’re more vulnerable to gas appliance pollution,” Craciun said.

Fighting for climate justice for vulnerable communities

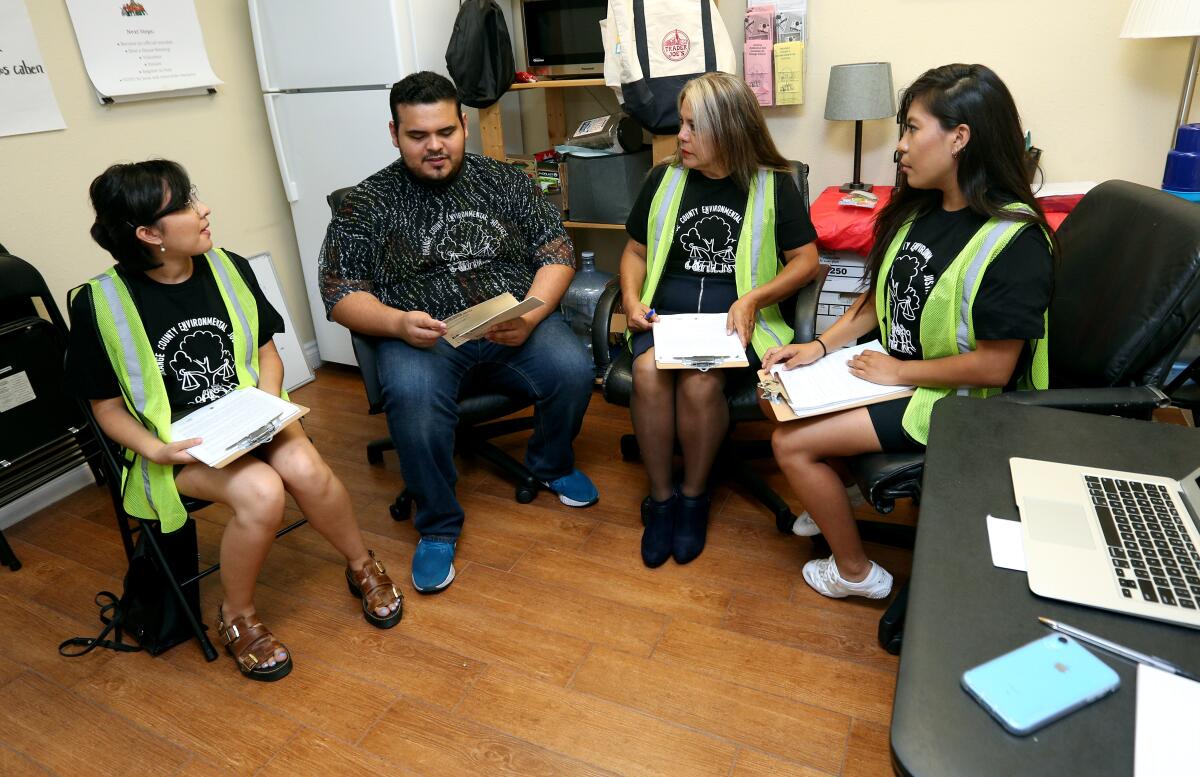

Orange County Environmental Justice has been advocating for low-income residents and communities of color in the county since it formed in 2016. For the group’s leader, Patricia Flores, climate change and environmental justice go hand in hand.

The issue of transitioning to electric cars becomes one about environmental justice with the knowledge that it was likely lead from gasoline that poisoned the soils of low-income communities in Santa Ana. The issue of industrial pollution becomes one about justice when coupled with the notion that many carbon-emitting businesses are located in poorer neighborhoods.

The group has been making its mark particularly in the majority-Latino city of Santa Ana, Orange County’s second largest city. One of its most significant efforts was uncovering that there is lead-contaminated soil throughout poor, predominately Latino neighborhoods in 2020.

Since then, the group has been trying to pressure the city to resolve the soil issue and provide care for the health of the vulnerable neighborhoods. It has engaged in talks with the city and Orange County Health Care Agency to make additions to Santa Ana’s general plan update. Flores said the plan currently includes a few crucial provisions, including increased blood-lead testing for children and a commitment to remediating the lead-contaminated soil.

Flores said the group is hoping to meet with the city within the next few weeks to show staff all of the specific policy changes they want in the general plan. She’s hoping that plan will include a healthcare provision for residents who have been impacted by lead but don’t have health insurance.

“A huge proportion of Santa Ana’s residents are undocumented, which means they don’t have access to state-provided health insurance — they don’t qualify for those services,” she said. “So that means there’s a huge amount of uninsured people in Santa Ana. And I believe that it’s the responsibility of the city and the county in a crisis like this, to provide those services.”

Orange County Environmental Justice also helped author and push through a sweeping climate change resolution last year in Santa Ana. The resolution included a commitment to 100% clean and renewable energy usage by 2045 and called for the city to continue looking into joining a CCE. It also took aim at the lead issue, with the city pledging to investigate and implement policies to limit or prevent exposure to lead and other environmental toxins.

In addition to its lead contamination and climate change policy initiatives, the nonprofit runs a water-monitoring project called Communities Organizing for Better Water. The program trains residents to be able to identify and document runoff pollution, particularly from industrial sites.

“Through that project, we’ve had a lot of success in being able to document issues of water quality in Anaheim, Santa Ana, Fullerton, Buena Park, Garden Grove and Orange,” she said.

As part of the executive leadership team of the Orange County Civic Engagement Table, a coalition of various progressive organizations, the group has also been working on changing the political makeup of Orange County through the redistricting process. It helped advocate for district maps for the Board of Supervisors that prioritized communities in Santa Ana, Anaheim and Fullerton impacted by environmental justice issues.

“We were also able to get the maps that we were advocating for passed as well at the congressional level, the state Assembly and state Senate last year,” Flores said. “So, that will ensure a lot of the communities impacted by environmental health issues in Santa Ana, Anaheim and Fullerton now have huge voting power, and candidates running in those districts are going to have to make sure to recognize those issues and create solutions if they want people to vote for them.”

Fighting to save the Orange County coastline from erosion

While the two other nonprofits have focused their efforts more inland, the South Orange County chapter of the national Surfrider Foundation has been working to save the county’s coastlines from erosion caused by climate change.

In recent years, rising sea levels and storms have eroded the sands of Capistrano Beach, and train tracks in San Clemente had to be temporarily shut down in September after large waves caused the ground to become unstable. Balboa Island also required drainage improvements to fortify it against high tides and rain.

Stefanie Sekich-Quinn, coastal preservation manager for the local Surfrider chapter, said it’s important for the group to focus on the ocean and coast because it doesn’t get much attention when it comes to climate change. Oceans absorb most of the heat from greenhouse gas emissions and excess carbon, which can have dramatic impacts on oceanic life.

“We feel like, oftentimes, the ocean and coasts have been kind of put aside when talking about climate change because of the more visual impacts of fires, extreme weather events, etc.,” she said. “But our ocean is literally at the center. It has absorbed 90% of the heat that’s been trapped in our atmosphere because of global warming and 30% of carbon. So that’s really huge.”

The chapter educates residents, amassing community support and pressing officials to enact policies that protect beaches from erosion. In San Clemente, it worked with the community to guide the city’s recent creation of a coastal resiliency plan.

The San Clemente City Council unanimously approved the plan in December to address shoreline erosion, coastal flooding and other consequences of potential rising sea levels. The plan is part of the city’s Local Coastal Program, which is partly funded by the California Coastal Commission and is required for all California coastal cities and counties. It is meant as a planning document to guide the city toward fortifying itself against a potential rise in sea levels expected as the effects of climate change worsen.

The group is also pushing for more substantial solutions to the extensive erosion at Capistrano Beach on the southern edge of Dana Point, which is owned by the city, Orange County Parks and the state. Currently, OC Parks has boulders and sandbags on the beach to deal with the rising tides, which Sekich-Quinn said exacerbates erosion due to blocking the natural flow of sediment.

“So watersheds and bluffs are how our beaches are made in Southern California — it’s a push inland out to the shore to build these beaches,” she said. “When there’s a seawall there, it just exacerbates that and then stops the sand from getting past it.”

Following pressure from Surfrider, OC Parks is now working on developing a “living shoreline” pilot program for Capistrano Beach. A living shoreline uses resources from the natural environment to fortify the coastline but allows the normal inland flow of sediment onto the beach. Sekich-Quinn described it as “using nature to protect nature.” Surfrider hopes the pilot project will become long-term.

Sekich-Quinn said there needs to be a paradigm shift in how governments manage coastlines and that they need to move away from traditional ideas of armoring coasts with boulders and rock revetments and look into novel solutions like living shorelines. But governments will need to realize there aren’t cheap and easy fixes to sea-level rise and erosion from climate change.

“It’s easy and cheaper, but it’s not as effective,” she said of the traditional methods. “When we say use Mother Nature to protect Mother Nature, it’s going to be more expensive than just throwing down a rock wall.”

Overall, Sekich-Quinn believes that although Orange County lags behind others in the state with regards to climate policy, cities are beginning to tackle the issue. There’s room for improvement, particularly when it comes to protecting the county’s beaches.

City leaders need to move forward with assessments of the vulnerability of their coasts and respond with adaptation plans to combat the destructive impacts of rising sea levels, said Sekich-Quinn.

“The reality is if we don’t get these sea-level rise plans in place,” she said, “it’s going to be extremely chaotic and destructive for our future community.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.