Santa Ana poet talks about coming of age in his debut poetry book ‘Flower Grand First’

There’s no way Gustavo Hernandez could have avoided writing about geography. A sense of place factored into his life from the start.

“You’re always so aware of the space that you’re inhabiting when you move from one place to another,” Hernandez said.

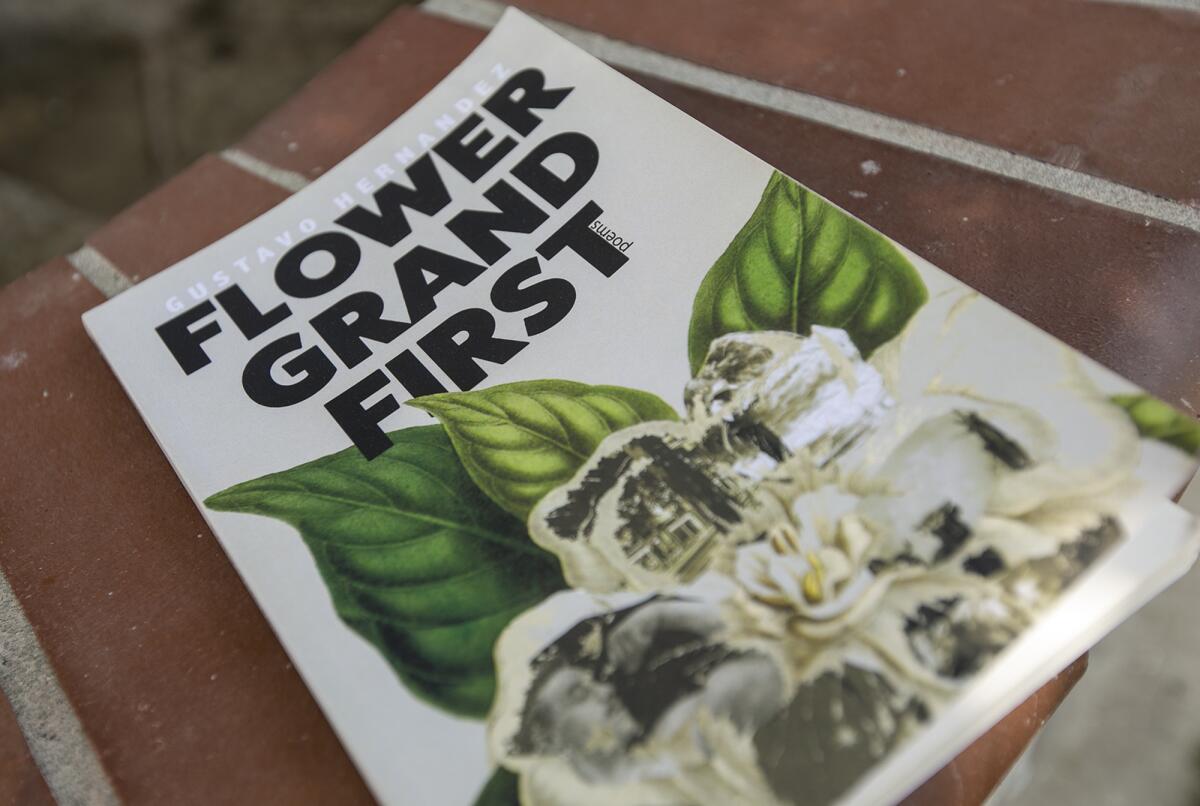

He immigrated from Jalisco, Mexico to Santa Ana with his parents in the 1980s. His dad was a landscaper, who had weed abatement contracts with Orange County. It made sense to write about where he was born and raised. It also made sense to collage a photo of his dad at work on the cover art of his first full-length poetry collection “Flower Grand First” (Moon Tide Press, $15).

In turn, the book has a special place at his mom’s house on an altar honoring his dad, who died last year while Hernandez was finishing up the book.

“Flower Grand First,” published last month, follows Hernandez’s coming-of-age story with an accompanying Spotify playlist that moves from “El Palomito” by Los Cadetes de Linares to “Caught a Lite Sneeze” by Tori Amos. The book serves as an elegy to his dad, his homeland and past versions of himself as he comes to terms with his sexuality and masculinity.

TimesOC caught up with Hernandez last week in between virtual book talks for students at Santa Ana Unified School District, the same place where he read some of the books that influenced his poetry collection.

In this edited and condensed conversation, Hernandez talks about the making of the book, Santa Ana, gay bars, body image and porn.

What has the past year been like for you?

The past year has been strange for everyone. I didn’t get to see a lot of my family for a long time. I was finishing up this book last year. After summer, I started writing the very last poems for it. It gave me some space to finish up the book in a way that was kind of cloistered. There weren’t a lot of real time things coming into the frame so I was able to let more of the past in, which is what I needed to close this book out. It was in the middle of all of this grief and death. This book also helped me grieve my dad and come to terms with my own mortality. It was just such a powerful sort of conclusion to the writing of this book.

Why did you choose “Flower Grand First” as the title?

Originally, the title was going to be “Just Bring Your Son.” It’s a line from a Tori Amos song. One of my mentors and the first person who took a look at the manuscript said he didn’t like the title. When my first publisher got a hold of the book, he sent some other titles to consider. I’m looking down at the list, and he is the one that put those three words together. It’s so fitting for the book because they’re streets of Santa Ana. They’re also streets in a lot of other big cities so it adds this universality to it. It also goes with the structure of the book. Flower as in beginning to grow. Grand, which is the middle section about coming to terms with my sexuality as an adult and sometimes there’s that aggrandizing we do when we’re in our 20s. First, is totally my dad. Whenever I think of La Primera [First Street], I remember being in his truck on that street.

Did you read other works about Jalisco and Santa Ana to draw inspiration or help you think about the landscape?

I can’t say that I did. “Las Tierras Flacas” by Agustín Yáñez played a big part, which is where the quote that opens the book comes from. Yáñez was governor of Jalisco, and the book deals with the rancho and the introduction of technology to a rural landscape. As far as my research about Santa Ana and Jalisco — that was all through my lived experiences here and the stories told to me by my parents. If there’s one image about writing this book that always comes to my mind, it’s me sitting in my parents’ frontyard listening to them tell me about the old world. It wasn’t so much the written word. It was the spoken word, the oral tradition.

There are so many poems about Santa Ana in different time periods of your life, but the poem “Santa Ana: Downtown” takes place in the present day. What was the inspiration for it?

I wrote it after reading a poem called “Nashville” by Tiana Clark. It is about Nashville, racism, cultural appropriation, capitalism and gentrification. Reading that poem, I was instantly energized. Tiana Clark is a magnificent poet. It was such a gorgeous piece of writing. I thought it was important to write my own poem about my hometown and the issues that we are facing today. I finished my shift at work, and I stayed to write it because I had been rolling it around in my head that day. It came out almost fully formed in half an hour. I wanted to talk about what it means to live in Santa Ana and see its progression as the year goes on and the shift as gentrification descended upon the city. You have this new revitalization and this exorcism of these things that are seen as not being serviceable.

I was drawn to the poems that reference bars or take place in bars. What is the significance of gay bars in your work and in your life?

That’s one of the parts that I feel the most strongly about in the book too because some of those are my favorite poems. I know it’s not the same for everyone as they’re coming out, but gay bars — less so now, more so when I was coming of age — they were really important. It’s a place where you go and know there are people who are gay, you’re going to be safe and you’re going to be able to be yourself. The first bars that I went to were gay bars. I didn’t go to a lot of straight bars. Sometimes questions of sobriety come up, and it’s very difficult for people to navigate. We wish there were more spaces that didn’t have alcohol as a central thing. But bars have always held this magical energy to me.

I still remember the first time I ever went to the Gauntlet. There’s a poem called “How To Be A Heartbreaker” that takes place at that bar. Now, it’s called the Eagle. I remember feeling like I found my community. I found people that looked like me. Going to bars in Orange County was a trip because the only gay bar that I remember was the Boom Boom Room in Laguna Beach. It was in this high-rent beach town, where there were all these people there who looked nothing like me. Going there for the first time, I was like, “Well, my life is over. I don’t fit in here. Is this what being gay is?” It wasn’t until I started discovering what you would consider the leather scene, that’s where I started seeing people who look like me, who I find attractive and who find me attractive. It was a big part of me coming into my own as a person, as a sexual entity. Maybe if you haven’t really struggled with your sexuality as much, a bar is just a bar. I never dated anyone when I was in high school. All of a sudden, here are these people I could possibly date, and it just opened up this different world.

There’s a progression that happens with your body from puberty in “Simpson-Mazzoli,” shame in “How to Be a Heartbreaker” and “Body” to a confidence in “Pecs.” How did you go from “How to Be a Heartbreaker” to “Pecs” in terms of your body and how you feel about it?

A lot of it came from being able to really look at myself, how to pay attention. In “How to Be a Heartbreaker” I’m trying to fit into all of these physical boxes, but I’m not really looking at what’s going on around me. I’m more concerned with what I think is the reality. It’s about where I found myself within the queer community and the roadblocks that exist in the community itself. I’ve struggled with my weight my whole life. This poem is more about how sometimes you walk into spaces and you’re not accepted because of your appearance so you try to reform yourself to become visible. The last line “Imagine above you/ a fat-cheeked boy, his belly keeping him/ there eternally, watching” — that’s how I felt at the beginning. It wasn’t that anyone was necessarily saying I’m not attractive or I’m too overweight. It was internalized traumas, internalized hatred for my own body because I wasn’t fitting into the Orange County Abercrombie & Fitch, six pack, blond hair, blue-eyed paradigm.

“Pecs” takes into account my body, immigration and my parents. A lot of the beauty that I perceive in myself, a lot of the acceptance and a lot of what makes me attractive has to do with my experiences, where I come from and the people around me. There is a broadening that happened between those two points where I’m not focused on one thing. I realized that love and acceptance comes from a lot of different places.

There’s a progression, and it took me a very long time. In the last seven years, I have come to love and appreciate my body. I’m heavier now than I’ve probably ever been, but I have never felt more attractive, which is a really crazy thing to think about when you torture yourself so much when you’re young.

“The Dirk Yates Guide To Naturalization” combines the identities of being an immigrant and gay into a poem full of references to porn. What was the inspiration behind it?

When I was a teenager all of this immigration stuff started happening where we became residents. At the same time, I was going through puberty, and I was discovering the idea of sex. I remember seeing this story about this scandal at the military base in Oceanside where Marines were making videos of themselves having sex and some man was producing them. I remember seeing that story on TV as my parents were getting ready to go to TJ [Tijuana]. I see the sign for that base when we’re driving back from TJ. It was just this crazy sort of thing that was rattling around in my head, and at the end of the day I wanted to someday be someone who is in charge of their own sexuality.

What are you working on next?

I hadn’t written anything since I finished the book in November, but I wrote my first poem in this new chapter of my writing career last week. The poem’s working title is “Monument.” I was thinking a lot about Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey where the main character is at rest after he’s gone on this journey. I’ve been thinking a lot about love and love sonnets. I’m not sure where it’s going to take me, but for now the person on the journey is at rest and is ready to reflect.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.